Timeline Contents

“The Story of the Bill of Rights,” Annenberg Classroom, September 13, 2018, https://youtu.be/MVtePB8Iu9E.

Bill of Rights ratified

December 15, 1791

The first 10 amendments to the U.S. Constitution laid out personal freedoms and government limitations.

Related Inquiry Packs:

Tape v. Hurley: Excluding Chinese students from public schools found unlawful

March 3, 1885

Anti-Chinese sentiment was high in California in the late 1800s. In 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act halting Chinese immigration and the naturalization of citizens of Chinese ancestry.

Mamie Tape, a student of Chinese descent, was denied admittance to her neighborhood public school despite a California law entitling all children admission to public schools.

The Tape family sued. Their case was ultimately decided in the California Supreme Court, which found the exclusion a violation of the state law and the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

Source: Library of Congress

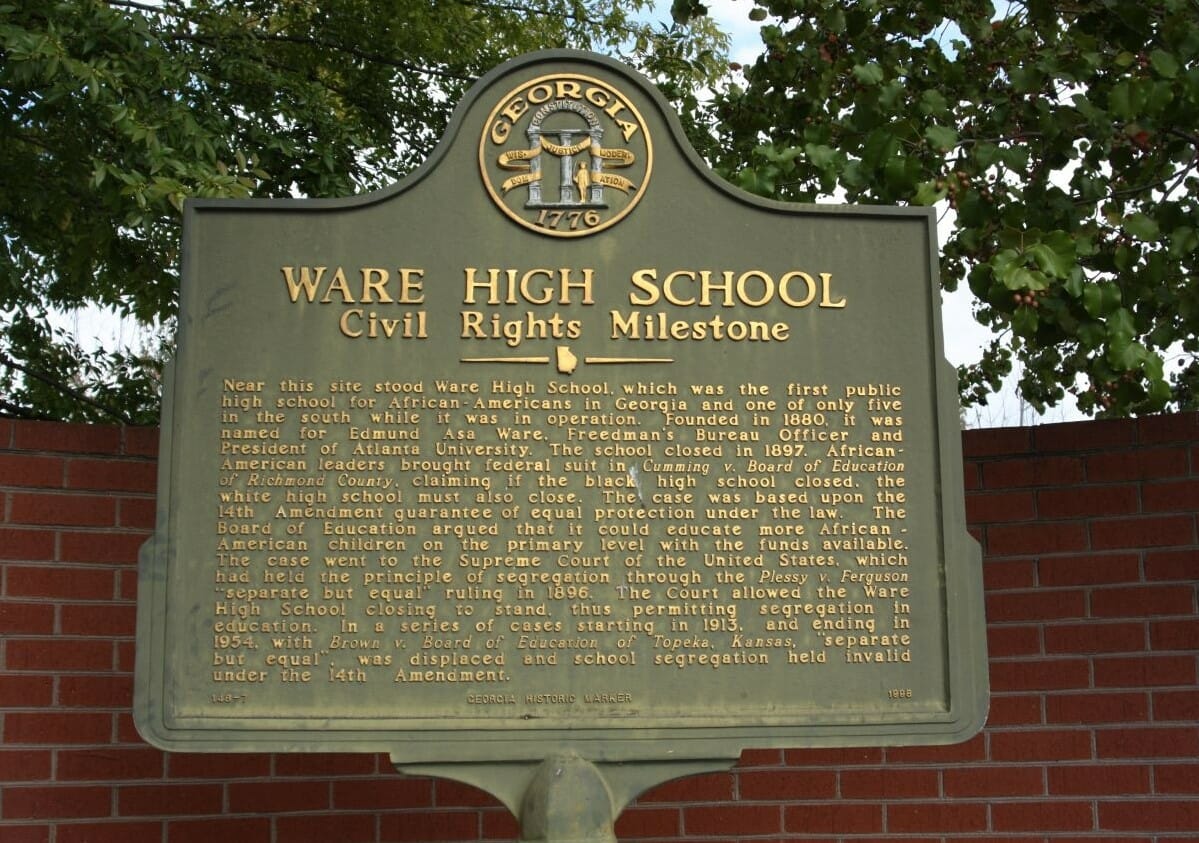

Cumming v. Richmond Co. Board of Ed.: Closing school for Black students found constitutional

December 18, 1899

In 1897, the Richmond County Board of Education decided to close the first and only African-American high school in Georgia—giving Black students no other option for obtaining a public education. A group of community members, including Joseph Cumming, filed a class action suit against the county. They argued that spending tax money to fund schools that were for White students only violated the 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause. The case was ultimately appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court decided to let the lower court’s decision stand, which allowed for the closing of the high school for Black students. The Supreme Court ruled that the 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause did not permit the federal government to intervene in state taxing and spending decisions. This decision sanctioned de jure segregation in public schools until it was overruled by Brown v. Board of Education (1954).

Source: Georgia Historical Society

Lum v. Rice: Excluding Chinese student from school found constitutional

November 21, 1927

Martha Lum, a student of Chinese ancestry, was excluded from a White-only school in Mississippi and told to attend the school for Black students. Her family challenged the assignment arguing that she was classified incorrectly as “colored.”

The U.S. Supreme Court decided for the school district that Lum could be excluded from the White-only school, declaring all racial segregation in schools was constitutional. This decision was overruled by Brown v. Board of Education (1954).

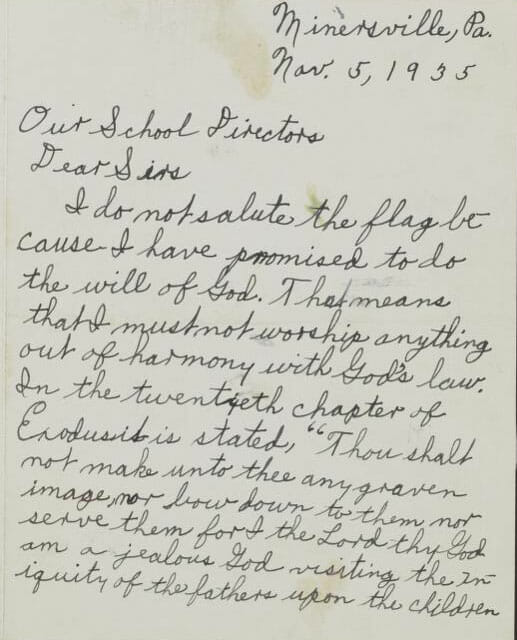

Minersville School District v. Gobitis: mandatory flag salute found constitutional

June 6, 1940

In Minersville (Pennsylvania) School District, students and teachers were required to salute the American flag. If they did not, they could be charged with insubordination and punished.

When two students were expelled for refusing to salute, they argued that the salute conflicted with their religious beliefs as Jehovah’s Witnesses. To them saluting was equivalent to idolatry, which is forbidden by their religion.

Their families challenged their expulsions as a violation of their First Amendment rights of freedom of speech and religion. The U.S. Supreme Court upheld the mandatory flag salute, finding that the state interest in national unity was compelling enough to permit the compulsory salute. This decision was overruled three years later in West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette (1943).

Source: Oyez

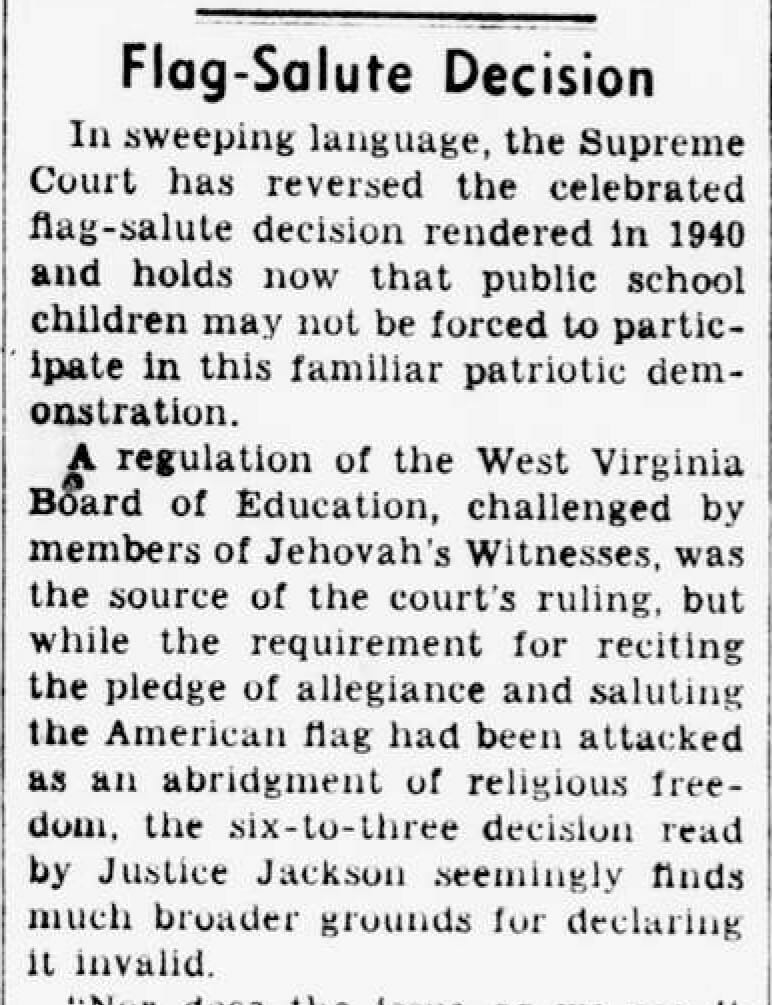

WV State Board of Ed. v. Barnette: mandatory flag salute violated the First Amendment

June 14, 1943

After the decision in Minersville School District v. Gobitis (1940), the West Virginia Board of Education adopted a resolution requiring that all public schools include a salute and pledge to the American flag as a part of their regular activities. Students and teachers were required to salute the flag, and if they did not, they could be charged with insubordination and punished.

A group of students who were Jehovah’s Witnesses, cited a religious objection to saluting the flag. It was their religious belief that saluting the flag was equivalent to idolatry, which is forbidden for Jehovah’s Witnesses. When the students were expelled for refusing to salute the flag, their parents sued the state board of education. They argued that the compulsory flag salute was a violation of the First Amendment, in effect asking that Minersville School District v. Gobitis (1940) be overruled.

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the compulsory flag salute was unconstitutional because it violated the Free Speech Clause of the First Amendment. It said that a flag salute was a form of speech because it was a way to communicate ideas. The Court explained that in most cases the government cannot require people to express ideas that they disagree with, especially when the ideas conflict with their own religious beliefs.

Sources: LandmarkCases.org and Oyez

Related Inquiry Packs:

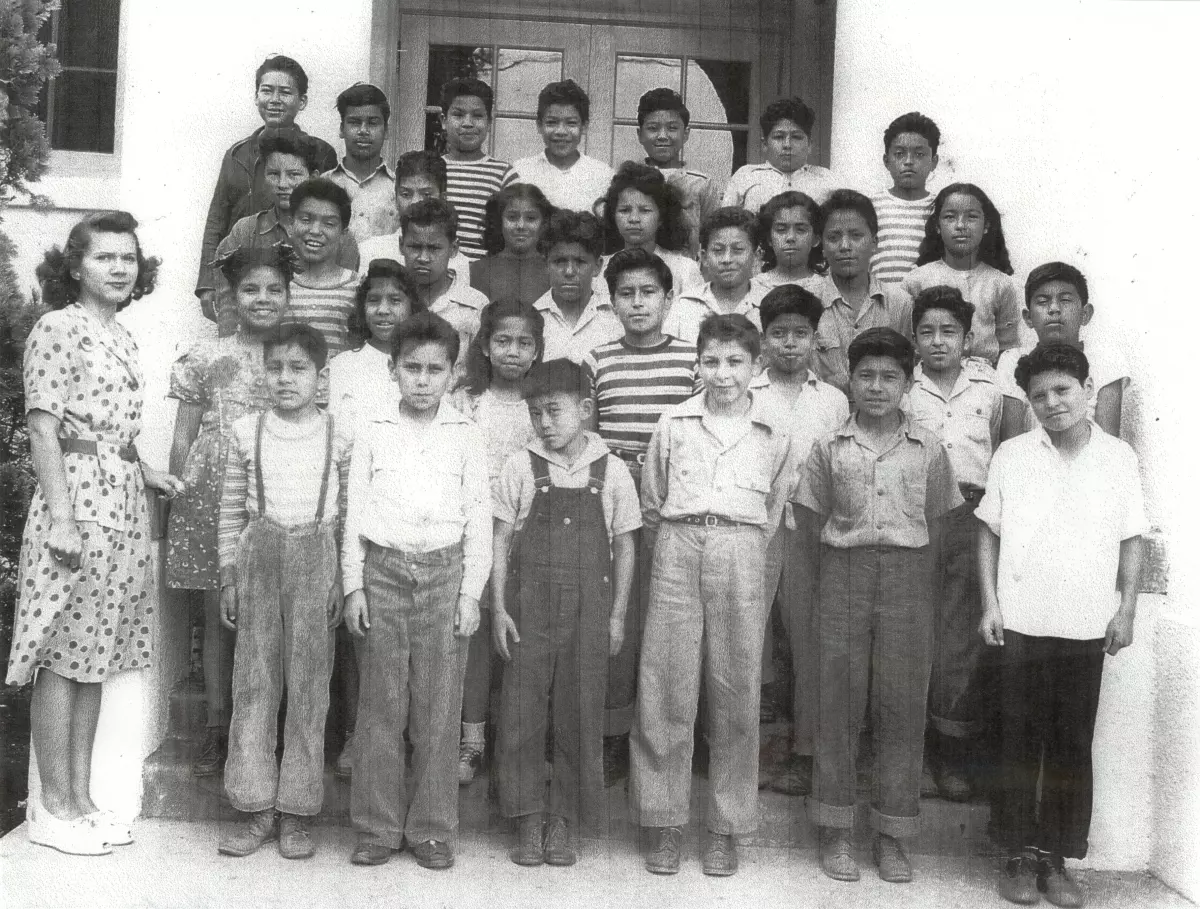

Mendez v. Westminster School District: segregation of Mexican American students found unconstitutional

February 18, 1947

Four California school districts refused to admit Mexican-American students to White-only public schools. A group of parents, including those of Sylvia Mendez, sued the school districts arguing that the exclusion of Mexican-American students was a violation of the 14th Amendment’sEqual Protection Clause. The case was appealed to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, which found the segregation unconstitutional. Two months later a law was passed making California the first state to desegregate public schools. The law was signed by Governor Earl Warren who would later serve as the Chief Justice of the United States when segregation in public schools was overruled in Brown v. Board of Education (1954). Source:National Archives

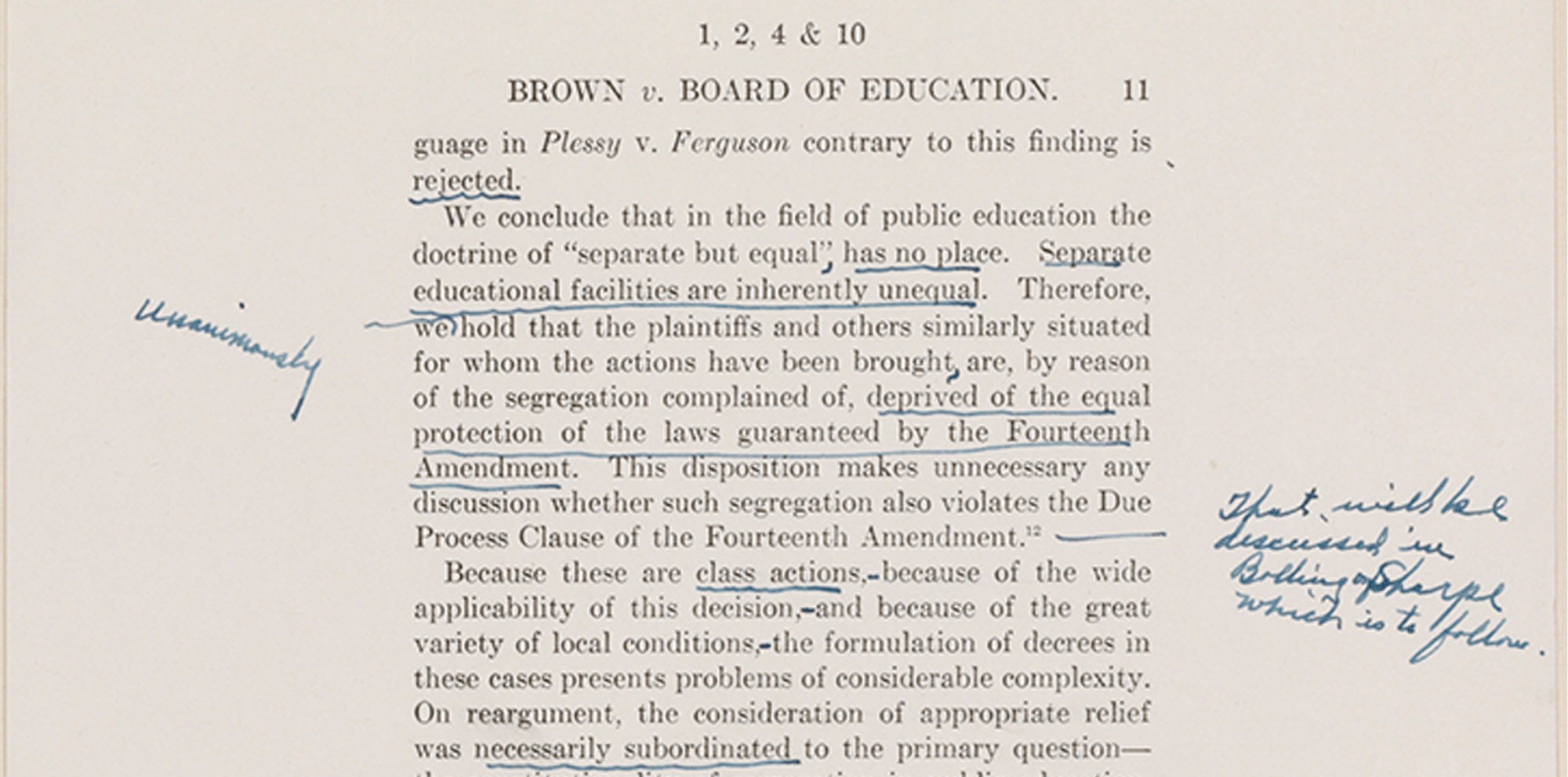

Brown v. Board of Ed. (I): segregation of public schools found unconstitutional

May 17, 1954

In the early 1950s, segregation in schools and other public facilities was legal because of past court decisions called precedents. In 1896, the Supreme Court of the United States decided a case, Plessy v. Ferguson, in which the Court said that segregation was legal when the facilities for both White and Black people were similar in quality. Under segregation, all-White and all-Black schools sometimes had similar buildings, busses, and teachers, but often they were of lower quality in all-Black schools. Black children often had to travel far to get to their school, passing White schools on the way.

In Topeka, Kansas, a Black student named Linda Brown had to walk through a dangerous railroad to get to her all-Black school. The Brown family believed that segregated schools should be illegal and sued the school system (Board of Education of Topeka). The case went to the U.S. Supreme Court asking: Does segregation of public schools based on race violate the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment? The Supreme Court found unanimously that segregated public schools violated the Equal Protection Clause. As a result of this decision, all public schools had to desegregate.

Source: LandmarkCases.org

Related Inquiry Packs:

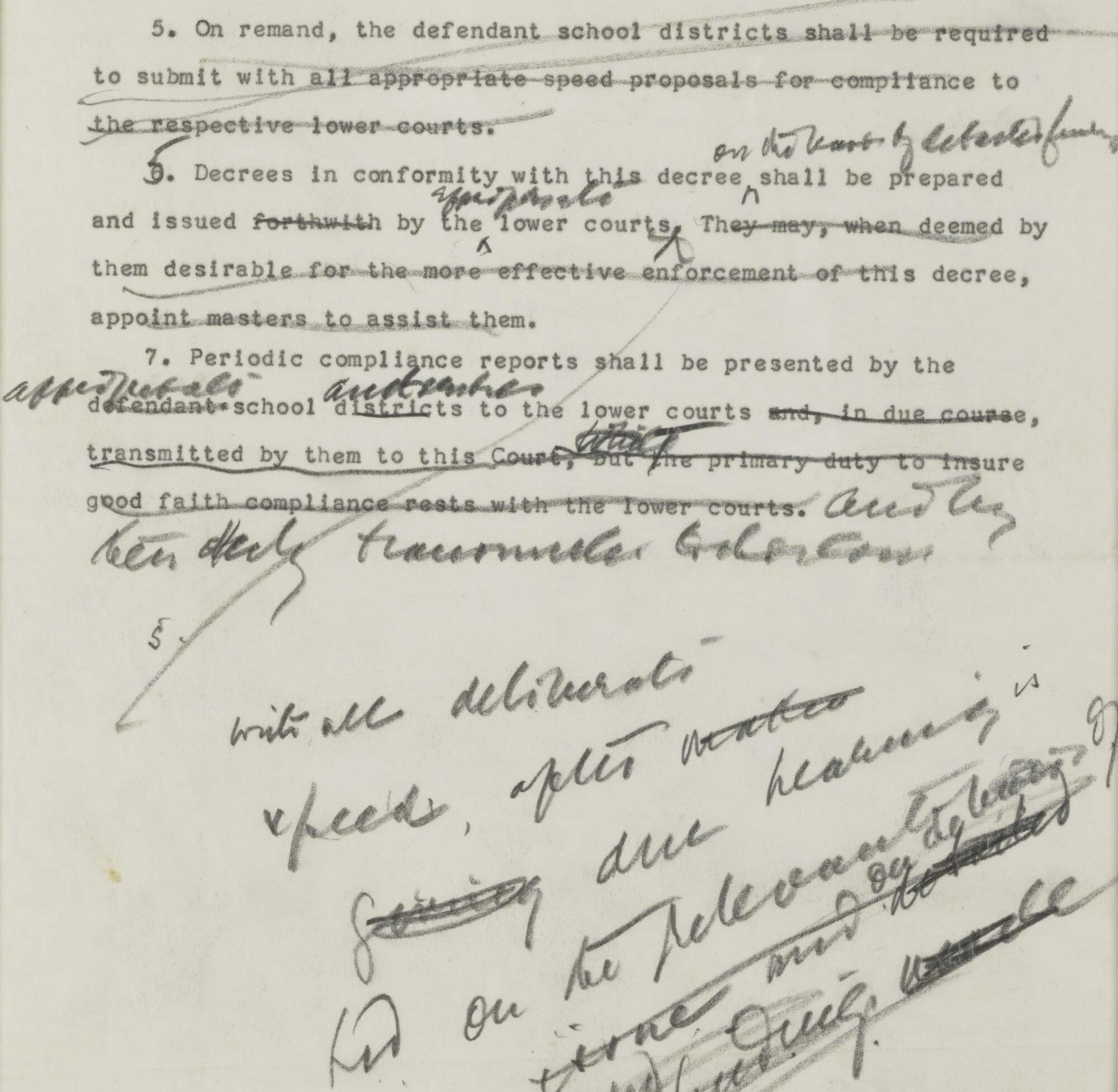

Brown v. Board of Ed. (II): Schools ordered to desegregate with “all deliberate speed”

May 31, 1954

After the Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas decision, in a show of resistance, several states did not immediately desegregate their public schools. In 1955, a second case, Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas II, directed schools and states to desegregate public schools “with all deliberate speed.” However, there was debate about exactly what “with all deliberate speed” meant. It was clear that it did not mean “immediately” and did not set a hard deadline for desegregation. The vagueness of this term may have encouraged some school districts to put off desegregation for years.

Source: LandmarkCases.org

Related Inquiry Packs:

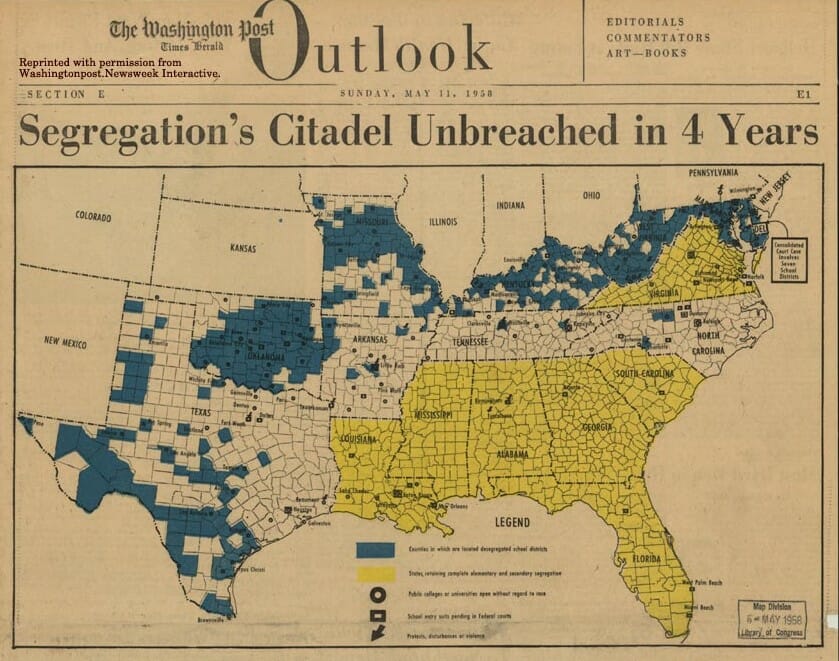

“Massive resistance” against desegregation

1956–1964

Senator Harry Byrd of Virginia coined the phrase “massive resistance” to describe the campaign waged by Southern states to resist desegregation after it was mandated by the Brown v. Board of Education decisions in 1954 and 1955.

Related Inquiry Packs:

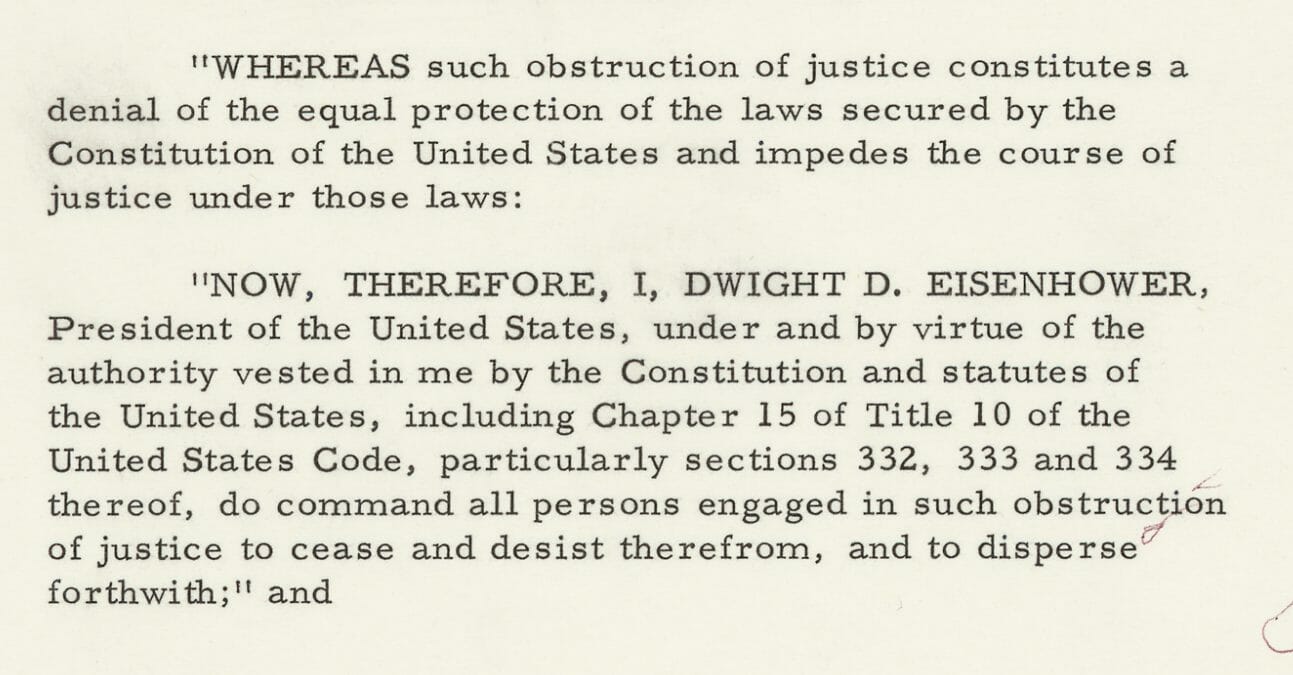

Executive Order 10730: Pres. Eisenhower used federal troops to enforce Brown decisions

September 23, 1957

Many states in the South participated in “massive resistance,” refusing to comply with the Brown decisions. In response, President Dwight D. Eisenhower issued Executive Order 10730. This action deployed federal troops to Little Rock, Arkansas, to enforce the Brown rulings by escorting Black students into Central High School.

Related Inquiry Packs:

Engel v. Vitale: school-sanctioned prayer in public schools found unconstitutional

June 25, 1962

In New York public schools, students and teachers started the day by reciting a prayer drafted by the state education agency, the New York State Board of Regents. The prayer was said aloud in the presence of a teacher, who either led the recitation or selected a student to do so. Students were not required to say this prayer out loud; they could choose to remain silent. Two Jewish families (including Steven Engel), a member of the American Ethical Union, a Unitarian, and a non-religious person sued their local school board. The families argued that reciting the daily prayer at the opening of the school day in a public school violated the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment.

The case was ultimately heard by the U.S. Supreme Court, which found for the families and ruled that the school-sponsored prayer was unconstitutional because it violated the Establishment Clause.

Source: Landmark Cases

Related Inquiry Packs:

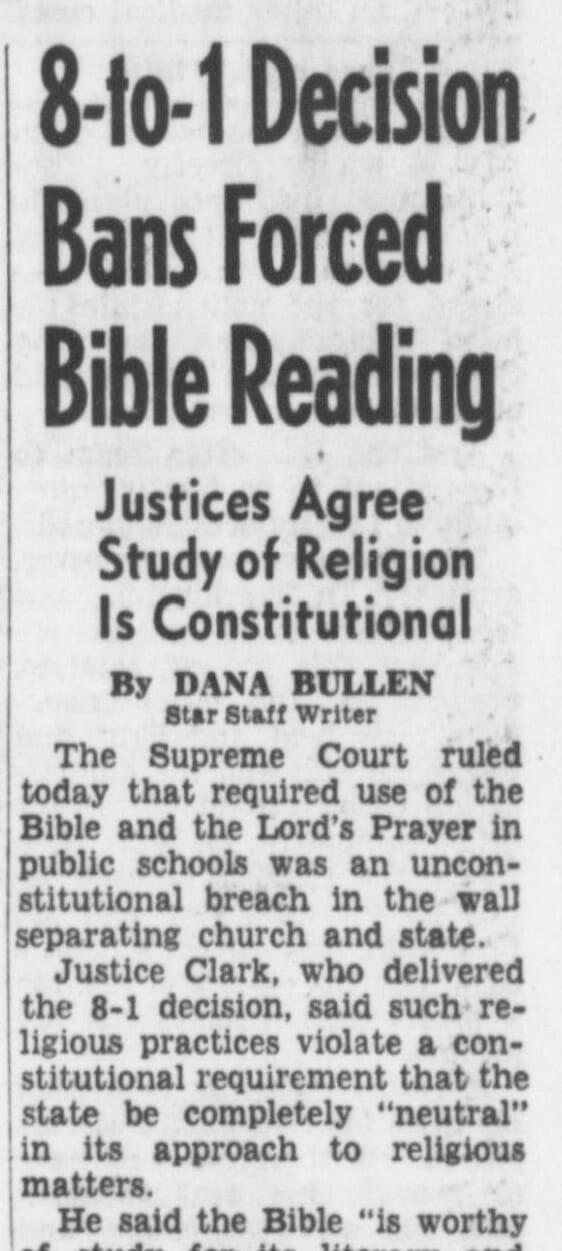

Abington School District v. Schempp: mandatory Bible reading in public schools found unconstitutional

June 17, 1963

A Pennsylvania law required Bible reading in public schools. Edward Schempp, on behalf of his children, sued to stop the enforcement of the law. Schempp argued that the law violated the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment.

The case made its way to the U.S. Supreme Court where it was joined with a case from Maryland in which a city rule required Bible reading and the recitation of the Lord’s Prayer in a public school. The Supreme Court ruled that conducting Bible readings and reciting the Lord’s Prayer in public schools violated the Establishment Clause.

Source: Oyez

Related Inquiry Packs:

Civil Rights Act of 1964: discrimination in schools is unlawful

July 2, 1964

Title IV of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 established that discrimination in schools on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin violates federal law.

Title VI of the act also prohibited schools receiving federal financial assistance (which is virtually all public schools) from discriminating against students based on race, color, or national origin.

Source: National Educational Association

Related Inquiry Packs:

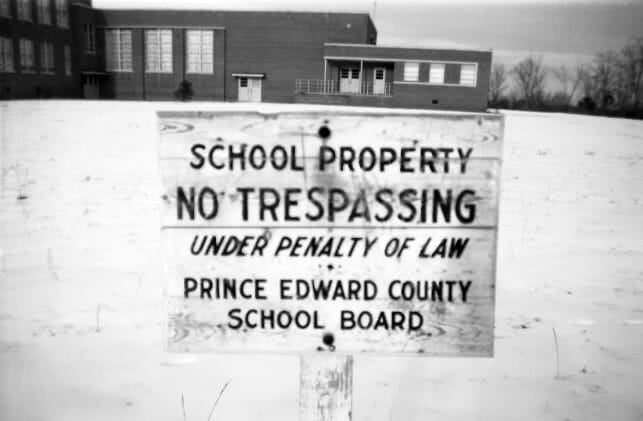

Griffin v. School Board of Prince Edward Co.: closing schools to avoid desegregation found unconstitutional

May 25, 1964

The phrase “massive resistance” was commonly used to describe the campaign waged by Southern states to resist desegregation after it was mandated by the Brown decisions.

When Prince Edward County, Virginia, was ordered to desegregate its public schools, it responded by not appropriating any money for the school system and forcing all public schools to close for five years. The county issued tuition vouchers for students to go to private schools—but there were no private schools for Black students. Therefore, Black students did not receive formal education from 1959 to 1963. Families sued Prince Edward County, arguing that the closing of the county’s public schools violated the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment.

The case ultimately went to the U.S. Supreme Court, which found for the families and ruled that the closing of the county’s schools denied Black students an education that was available to White students. Because the schools were closed for the express purpose of denying education to a group of children based on race, the action violated the Equal Protection Clause.

Source: Oyez

Related Inquiry Packs:

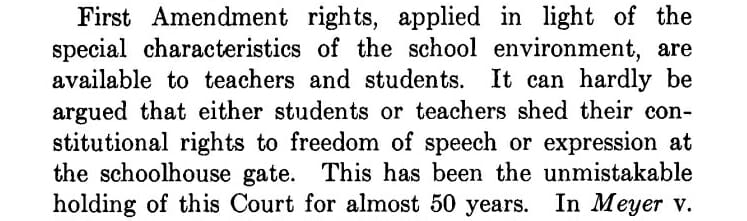

Tinker v. Des Moines: symbolic speech is protected in public schools

February 24, 1969

Students John and Mary Beth Tinker and Christopher Eckhardt opposed the war in Vietnam. To show their opposition, they planned to wear black armbands to school. Having learned about the students’ plan, Des Moines principals adopted a new policy prohibiting armbands. Despite the new policy, the students wore armbands to school and were suspended.

The students and their parents challenged the suspensions as a violation of the Free Speech Clause of the First Amendment. They argued that the wearing of armbands was peaceful symbolic speech, which should be protected just as verbal speech is.

The case made its way to the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled in favor of the students. It made clear that students do not “shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.” The Court found that the symbolic wearing of armbands was speech. To restrict speech, a school must demonstrate that the speech would “materially and substantially interfere” with the work of the school or interfere with the rights of other students. School officials in Des Moines, the Court explained, could not “reasonably forecast” that the students’ speech would cause a substantial disruption or invade the rights of others.

Source: LandmarkCases.org

Related Inquiry Packs:

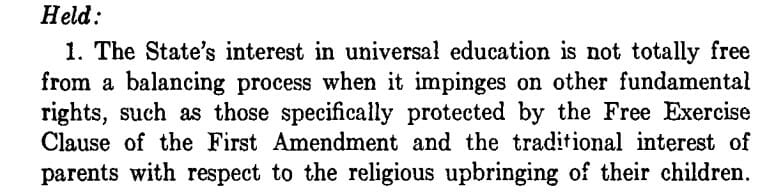

Wisconsin v. Yoder: right to worship freely outweighed state’s interest in forcing school attendance

May 15, 1972

A Wisconsin law made school attendance compulsory until the age of 16. When their children stopped attending public school after eighth grade, parents of Amish students were prosecuted for violating the law, convicted at trial, and fined. The parents appealed arguing that the law violated their religious beliefs, endangered their salvation, and was unnecessary for their simple way of life. In these ways compulsory education was a violation of the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment.

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled for the parents that their free exercise of religion to direct the religious upbringing of their children outweighed Wisconsin’s compelling interest in requiring school attendance after eighth grade.

Source: Oyez

![Title-IX.jpg Warren K. Leffler, “Women's lib[eration] march from Farrugut Sq[uare] to Layfette [i.e., Lafayette] P[ar]k,” Photograph, August 26, 1970. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, https://www.loc.gov/resource/ppmsca.03425/.](https://legaltimelines.org/wp-content/media/2023/02/Title-IX.jpg)

Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972

June 23, 1972

Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 protects people from discrimination based on sex in education programs or activities that receive federal financial assistance. Title IX states: “No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.”

Source: U.S. Department of Education

Related Inquiry Packs:

Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act of 1974

August 21, 1974

The Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act of 1974 (FERPA) is a federal law that protects the privacy of students’ educational records and gives parents and students the right to review records. FERPA applies to all schools that accept federal funds.

Source: U.S. Department of Education

Equal Educational Opportunities Act of 1974

1974

The Equal Educational Opportunities Act of 1974 (EEOA) requires schools to address language barriers that could impact a student’s ability to participate equally in instruction and programming.

EEOA states: “No state shall deny equal educational opportunity to an individual on account of his or her race, color, sex, or national origin, by ... the failure by an educational agency to take appropriate action to overcome language barriers that impede equal participation by its students in its instructional programs.”

The EEOA also requires schools to take steps to ensure that students with limited English language skills may still participate equally in all school programs.

Source: National Education Association

Related Inquiry Packs:

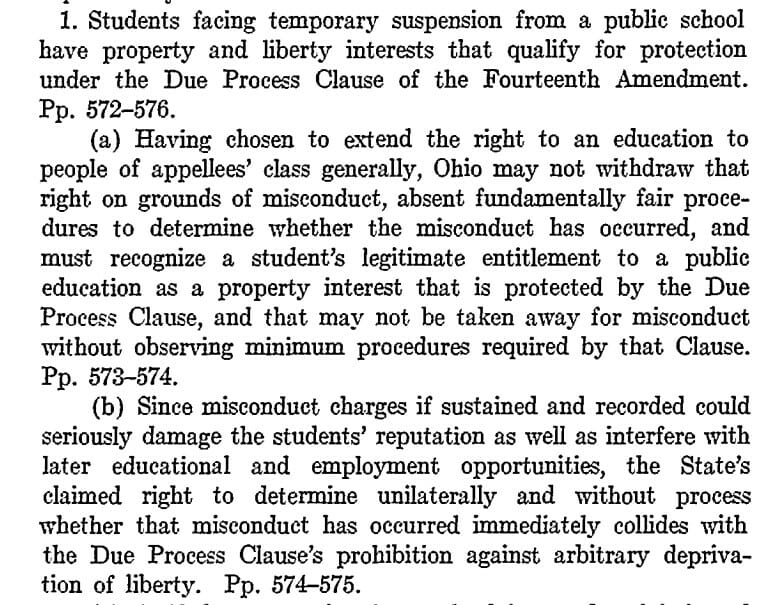

Goss v. Lopez: students facing disciplinary measures must have due process

January 22, 1975

A group of students, including Dwight Lopez, were suspended from their Columbus, OH, schools for 10 days for the destruction of property and disrupting the learning environment. The principal did not grant the students preliminary hearings before issuing the suspensions, and Ohio law did not require such hearings be held.

The principal's actions were challenged in court. The case ultimately made its way to the U.S. Supreme Court asking if the imposition of the suspensions without hearings violated the students’ due process rights guaranteed by the 14th Amendment.

The Court ruled that suspensions without a basic and informal hearing, which includes notice and an opportunity to respond, violated the students’ 14th Amendment rights.

Source: Oyez

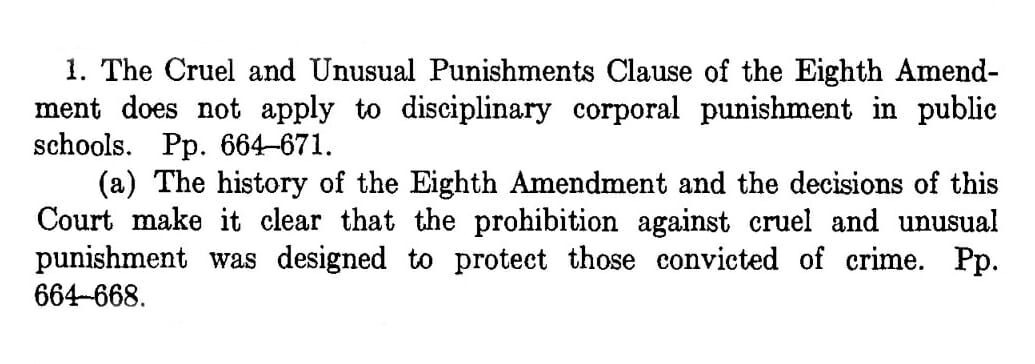

Ingraham v. Wright: 8th Amendment does not protect against corporal punishment

April 19, 1977

Dade County schools in Florida had a discipline policy that allowed for corporal punishment. Students at two different schools were paddled for various offenses including tardiness. The families of two of the students filed complaints against the principals of the schools and the school superintendent.

The case was ultimately decided by the U.S. Supreme Court, where the students argued that the cruel and unusual punishment clause of the Eighth Amendment forbade corporal punishment.

The Court found for the principals and ruled that the Eighth Amendment does not prevent corporal punishment in public schools. The Court considered earlier decisions about corporal punishment in schools that found teachers could impose reasonable punishments on their students. It also explained that the Eighth Amendment refers only to criminal punishments, not school disciplinary actions.

Source: Oyez

Plyler v. Doe: Civil Rights Act protects students who have entered country illegally

June 18, 1982

A Texas state law prohibited the use of state funding for the education of immigrants who entered the country illegally. It also permitted schools to deny admission to students not legally admitted to the United States. The Texas law was challenged as a violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment because it prevented children who are living in the United States illegally from receiving a free, public education.

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Texas’s law violated the Equal Protection Clause. It explained that students living in the United States without legal permission are protected by civil rights laws such as Titles IV and VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 which prohibits discrimination based on race and national origin.

Source: National Education Association

Related Inquiry Packs:

Equal Access Act of 1984

August 11, 1984

The Equal Access Act of 1984 prohibits publicly funded schools from denying students the ability to meet due to the “religious, political, philosophical, or other content of the speech at such meetings.”

Source: The First Amendment Encyclopedia (Middle Tennessee State University)

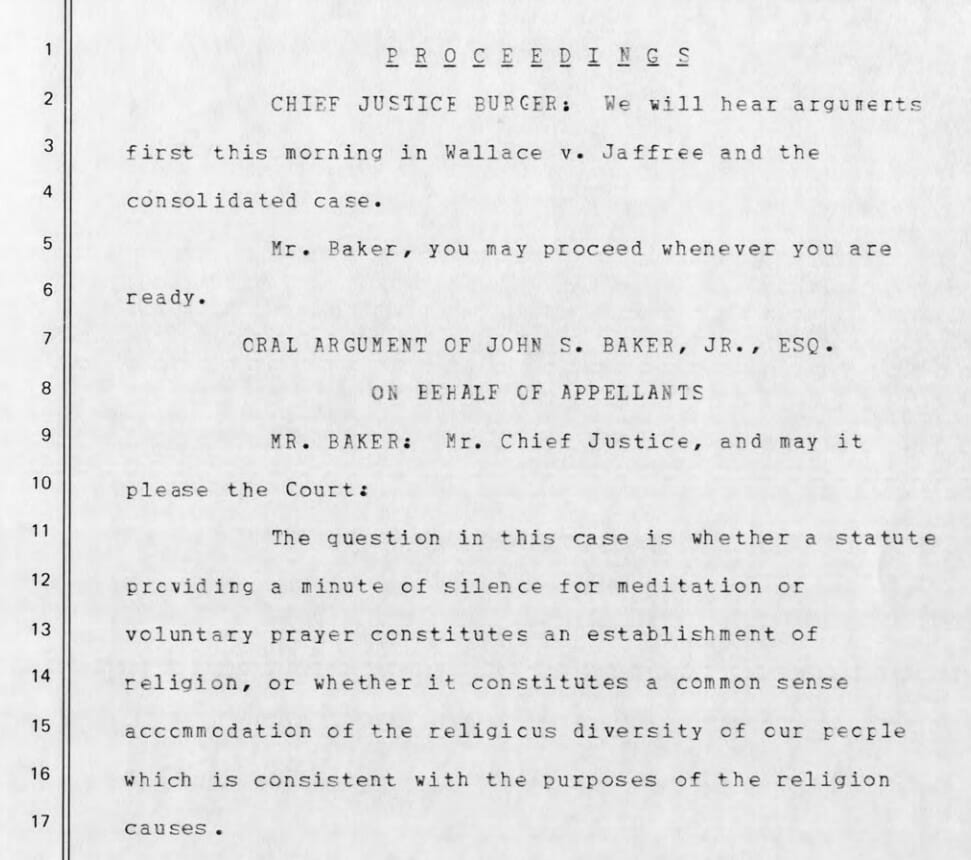

Wallace v. Jaffree: law mandating moment of silence in schools found unconstitutional

June 4, 1985

Alabama enacted a law that mandated schools to observe a daily moment of silence that students could opt to use for prayer or meditation. Ishmael Jaffree, the father of three children who attended public schools in Alabama, challenged the law, citing that it violated the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment.

The case went to the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled that the Alabama law lacked any non-religious purpose and was enacted as a way of establishing and endorsing religion in public schools. Therefore, the law violated the First Amendment’s Establishment Clause.

Sources: First Amendment Encyclopedia (Middle Tennessee State University) and Oyez

Related Inquiry Packs:

Bethel School District v. Fraser: lewd speech can be restricted in public schools

July 7, 1986

During a school assembly at Bethel High School in Washington state, Matthew Fraser gave a speech to nominate a classmate for student government. The short speech was filled with sexual references and innuendoes. The students reacted to the speech with hoots, cheers, and lewd motions. Fraser was suspended for three days. The Fraser family challenged their son’s suspension as a violation of his First Amendment right to free speech.

The case was ultimately decided in the U.S. Supreme Court. Ruling in favor of the school district, the Court emphasized that students do not have the same First Amendment rights as adults. It explained that school officials may prohibit the use of lewd, indecent, or plainly offensive language, even if it is not obscene. Schools have an interest in preventing speech that is inconsistent with the school’s “basic educational mission” and in “teaching students the boundaries of socially inappropriate behavior.

Source: Street Law, Inc.

Related Inquiry Packs:

McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act

July 22, 1987

The McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act is a federal law created to support the enrollment and education of students experiencing homelessness by removing as many barriers to learning as possible.

Source: U.S. Congress

Related Inquiry Packs:

Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier: school has editorial control of student newspapers

January 13, 1988

As a practice, Hazelwood East High School’s principal reviewed the school’s student-written newspaper before publication. In 1983, he decided to have certain pages pulled because he considered the content in two of the articles to be too sensitive. He acted quickly to remove the pages in order to meet the paper’s publication deadline. Three former student journalists who worked on the paper, including Cathy Kuhlmeier, sued the school district, arguing that this censorship was a direct violation of their First Amendment right to free press.

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled against the students explaining that the First Amendment does not prevent school officials from exercising reasonable authority over the content of school-sponsored publications.

Source: LandmarkCases.org

Westside Community Schools v. Mergens: religious clubs must have an equal opportunity as extracurricular activity

June 6, 1990

A group of public high school students sought permission to form an extracurricular Christian club. The school’s administration refused, citing the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment and the club’s lack of a faculty sponsor. The school feared allowing the club would be seen as an endorsement of religion. The students’ families sued the school for violating the Equal Access Act, which prohibits schools from denying students the ability to meet due to the religious, political, philosophical content, or speech.

The case was decided by the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled in favor of the students. They stated that since the high school permitted other extracurricular clubs and students were not forced to join, it did not violate the Establishment Clause. Therefore, the school must abide by the Equal Access Act even though the club’s discussions would be about religious topics.

Source: Oyez

Related Inquiry Packs:

Individuals with Disabilities Education Act

October 30, 1990

President George H.W. Bush signed the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) into law. IDEA guarantees students with disabilities a “free appropriate public education,” providing them with the same opportunity for education as other public school students. This law mandates “Individualized Education Programs” and the “least restrictive environment” for qualifying special education students.

Source: U.S. Department of Education

Related Inquiry Packs:

Lee v. Weisman: clergy-led prayers at public school ceremonies found unconstitutional

June 24, 1992

A principal in Providence, Rhode Island, invited a rabbi to deliver prayers at the middle school graduation. The principal advised the rabbi that both the opening and closing prayers should be nonsectarian. However, the rabbi repeatedly thanked “God” and concluded as follows: “[w]e give thanks to You, Lord, for keeping us alive, sustaining us and allowing us to reach this special, happy occasion.” The family of student Deborah Weisman sued the school for violating the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment.

The case was decided by the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled for Weisman agreeing that the prayer violated the Establishment Clause. The Court explained that the school’s control over the ceremonies placed both public and peer pressure on students to stand or remain silent during the prayer.

Source: LandmarkCases.org

Related Inquiry Packs:

Vernonia v. Acton: drug testing student athletes found constitutional

June 26, 1995

Vernonia School District in Oregon had a drug problem. An investigation showed that student-athletes were among those using illegal drugs, so the school district began a program of random urinalysis drug testing on student-athletes. A student going out for the football team, James Acton, refused to consent to the testing. The Acton family challenged the policy as a violation of James Acton’s Fourth Amendment protection against unreasonable search.

The case was decided by the U.S. Supreme Court in favor of Vernonia School District. The Court weighed the intrusiveness of the search and the school district’s legitimate interest in maintaining safety. The Court ruled that the search was reasonable because urinalysis is not overly intrusive and the safety concerns of ensuring athletes are not under the influence of drugs is a legitimate interest of the school district.

Source: LandmarkCases.org

Related Inquiry Packs:

Pottawatomie School District v. Earls: drug testing students who participate in extracurriculars found constitutional

June 27, 2002

In Tecumseh, Oklahoma, a school district adopted the policy of requiring consent to random urinalysis drug testing by students involved in extracurricular activities.

Two Tecumseh High School students and their parents sued the school district arguing the policy was a violation of the students’ Fourth Amendment protection against unreasonable search.

The case was decided by the U.S. Supreme Court in favor of the school district. Like in an earlier case about drug testing of student athletes, Vernonia School District v. Acton (1995), the Court weighed the intrusiveness of the search and the school district’s legitimate interest in maintaining safety. The Court ruled that the search was reasonable because preventing drug use is a legitimate interest of the school district, and the school’s role in regulating extracurricular activities meant a lowered expectation of privacy for the students.

Source: Oyez

Related Inquiry Packs:

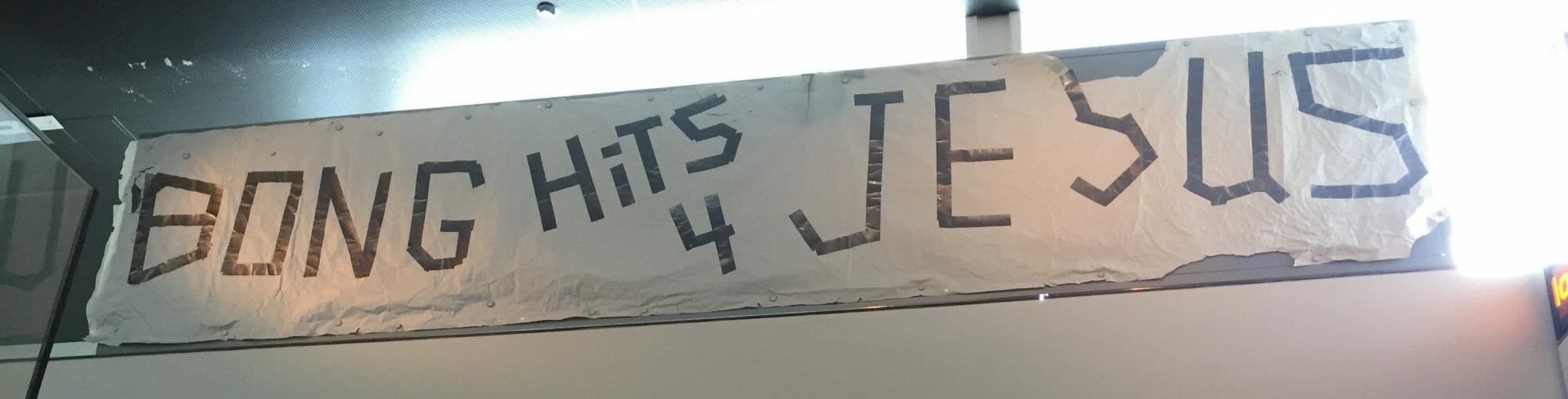

Morse v. Frederick: schools may regulate speech that promotes drug use

June 25, 2007

A school in Alaska took students on a walking-field trip to watch the Olympic torch passing nearby their school. Joseph Frederick, a student, did not come to school that day but joined his classmates at the field trip and unfurled a banner reading “BONG HiTS 4 JESUS.” The school’s principal, Deborah Morse, suspended him for displaying a banner that advocated drug use. Frederick, who claimed he was not in school at the time, sued the administration for violating his First Amendment right to free speech.

The case was ultimately decided by the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled for the school’s principal, concluding that she did not violate the First Amendment by confiscating a pro-drug banner. The Court dismissed Frederick’s argument that this case did not involve school speech because he was not at school. It emphasized that the field trip was approved by the school, monitored by teachers, and occurred during school hours, and, although he did not report to school, he was present at the event. The Court ruled it was reasonable for the principal “to conclude that the banner promoted illegal drug use—in violation of established school policy.”

Source: LandmarkCases.org

Related Inquiry Packs:

Safford Unified School District v. Redding: strip searching students for non-illicit drugs found unconstitutional

June 25, 2009

Savana Redding was a middle school student in Arizona who was accused of having ibuprofen (Advil) in violation of a school policy. She was taken to the nurse’s office and made to undress for a strip search. Redding’s mother sued the school, challenging the search as a violation of the protection against unreasonable searches in the Fourth Amendment.

The case was decided by the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled that the school violated Redding’s Fourth Amendment rights when school officials conducted the strip search. The Court noted there was enough suspicion to justify a search of Redding’s bag and outer clothing, but not enough to warrant a strip search. But because there was not a reasonable suspicion of danger to students nor a reasonable suspicion that Redding was hiding the ibuprofen in her underwear, the strip search exceeded the “reasonable suspicion” standard set out in New Jersey v. T.L.O. (1985).

Source: Street Law, Inc. Resource Library

Related Inquiry Packs:

Mahanoy Area School District v. B.L.: off-campus speech is protected

June 23, 2021

B.L. was a cheerleader at Mahanoy Area High School in Pennsylvania. On Saturday while off campus, B.L. posted a message on Snapchat. Her snap was a picture of B.L. and a friend with their middle fingers raised and the caption, “F*** school f*** softball f*** cheer f*** everything.” (Note: B.L. did not use *** and wrote out the full word.) The cheerleading coaches determined that B.L. violated their code of conduct and removed her from the team for the school year, but she faced no further disciplinary action. B.L.’s parents filed a lawsuit against the school district alleging that B.L.’s First Amendment right to free speech was violated because the school disciplined her for off-campus speech.

Ultimately the case went before the U.S. Supreme Court to decide whether the precedent set in Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District (1969), that public school officials may regulate speech that would substantially disrupt the work of the school, applies to student speech that occurs off campus. The Court ruled in favor of the student (B. L.), finding that the school violated her First Amendment rights by punishing her for off-campus speech without providing an interest “substantial” enough for doing so.

Source: LandmarkCases.org

Related Inquiry Packs: