Timeline Contents

Magna Carta signed: foundation for basic rights and liberties

June 15, 1215

Semayne’s Case: 4th Amendment origins

January 1, 1604

This English common law case served as the origin of American Fourth Amendment rights. Sir Edward Coke said in the case: “The house of every one is to him as his castle and fortress, as well for his defense against injury and violence as for his repose.” The case limited the King’s authority to conduct searches in peoples’ homes, but it allowed some searches and seizures to be conducted under certain conditions, including that a search warrant was obtained.

Source: Online Library of Liberty

First recorded execution in the colonies

December 1, 1608

The death penalty was a punishment in Britain that came to the colonies early on. In 1608, Captain George Kendall was shot for being a Spanish spy in the Jamestown settlement.

Source: Annenberg Classroom

English Bill of Rights approved

December 16, 1689

This act defined basic civil rights in England. The English Bill of Rights resulted from a revolution to overthrow King James II. When the new king came into power, the House of Commons (the lower house of British Parliament) passed the act. It recognized several rights that would later align with the U.S. Bill of Rights, including freedom from excessive bail and fines and no cruel and unusual punishment.

Source: British Library

Government given broad authority to detain Black people

1693-1865

As early as 1693, colonies made laws that allowed government officials to detain Black people, both free and enslaved. In Philadelphia, a law allowed police to stop any Black person if they were seen in public. Later, “slave” patrols were given authority to detain enslaved people who had run away from their enslavers and to control other acts of resistance by enslaved people, often violently. Even after the passage of the Bill of Rights almost 100 years later in 1791, Black people could be detained without access to basic rights because they were not considered citizens. Legally, enslaved people were not even considered people; they were considered to be property.

Sources: American Bar Association and “Let This Voice Be Heard” by Anthony Benezet, Father of Atlantic Abolitionism

Virginia Declaration of Rights adopted

June 12, 1778

Drafted by George Mason and adopted by the Virginia Constitutional Convention on June 12, 1776, the Virginia Declaration of Rights protected freedoms, including the right to:

- a speedy trial by an impartial jury

- freedom of the press

- freedom of religion

- be protected against cruel and unusual punishments

- be protected against excessive bail and fines

- be protected from baseless search and seizure

- be “confronted with the accusers and witnesses, to call for evidence in his favor”

- not be “compelled to give evidence against himself”

- not be “deprived of his liberty except by the law of the land”

Thomas Jefferson borrowed heavily from the Virginia Declaration of Rights when writing the Declaration of Independence. It was also the inspiration for much of the U.S. Bill of Rights.

Source: National Archives

Anti-death penalty campaigns began

1790 through the 1800s

From the 1790s through the 1800s, many states clearly defined and limited what crimes could be punished with the death penalty. Pennsylvania repealed the death penalty for all crimes except first-degree murder in 1794, and it later became the first state to stop public executions. Tennessee changed its laws in 1829 so that there were no mandatory sentences that condemned someone to death.

“The Story of the Bill of Rights,” Annenberg Classroom, September 13, 2018, https://youtu.be/MVtePB8Iu9E.

Bill of Rights ratified

December 15, 1791

Based on English common law, the Magna Carta, the English Bill of Rights, and the Virginia Declaration of Rights, these first 10 amendments to the U.S. Constitution laid out personal freedoms and government limitations.

Source: Congress.gov

Related Inquiry Packs:

“Marbury vs. Madison: The Empowerment of the Judiciary,” Supreme Court Historical Society, October 19, 2022, https://youtu.be/jqiHy4QSdqg

Marbury v. Madison: Supreme Court has power of judicial review

February 24, 1803

At the end of President John Adams’ term, his secretary of state failed to deliver documents commissioning William Marbury as justice of the peace in the District of Columbia. Once President Thomas Jefferson was sworn in, he told James Madison, his secretary of state, not to deliver the documents to Marbury and others in order to keep members of the opposing political party from taking office. Marbury sued Madison asking the Supreme Court to issue a writ (order) requiring him to deliver the documents necessary to officially make Marbury justice of the peace. The Supreme Court chose not to answer Marbury’s question, but rather asked whether it had the jurisdiction to issue the writ. The Marbury v. Madison decision resulted in the establishment of the concept of judicial review. As a result of this case, the Supreme Court obtained the power to overturn federal and (later) state laws and practices that violate the Constitution.

Source: LandmarkCases.org

Supreme Court made several 8th Amendment rulings

1878-1910

In two cases during this period, the Supreme Court ruled that execution by public shooting and execution by the electric chair were not considered cruel and unusual punishment. In a third case, Weems v. United States (1910), the Court ruled that if a punishment is too harsh for a crime, it can be considered cruel and unusual punishment. In Weems, a government official in the U.S. territory of the Philippines was found guilty of falsifying documents. He was initially sentenced to 15 years in prison, hard labor, lifetime surveillance, the loss of the rights to vote and own property, and more. The Supreme Court ruled that this was cruel and unusual punishment because the punishment did not fit the severity of the crime.

Source: Annenberg Classroom

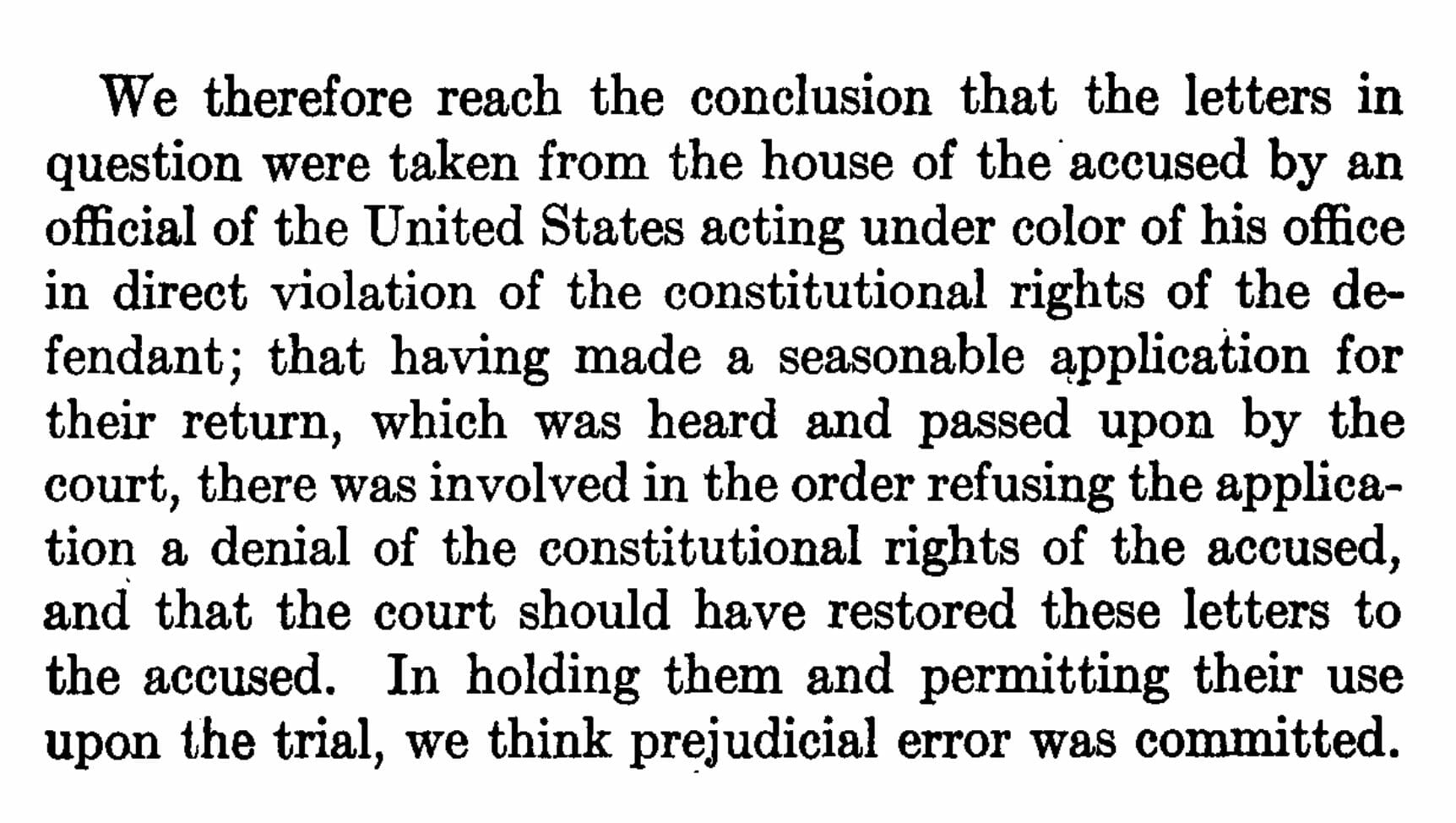

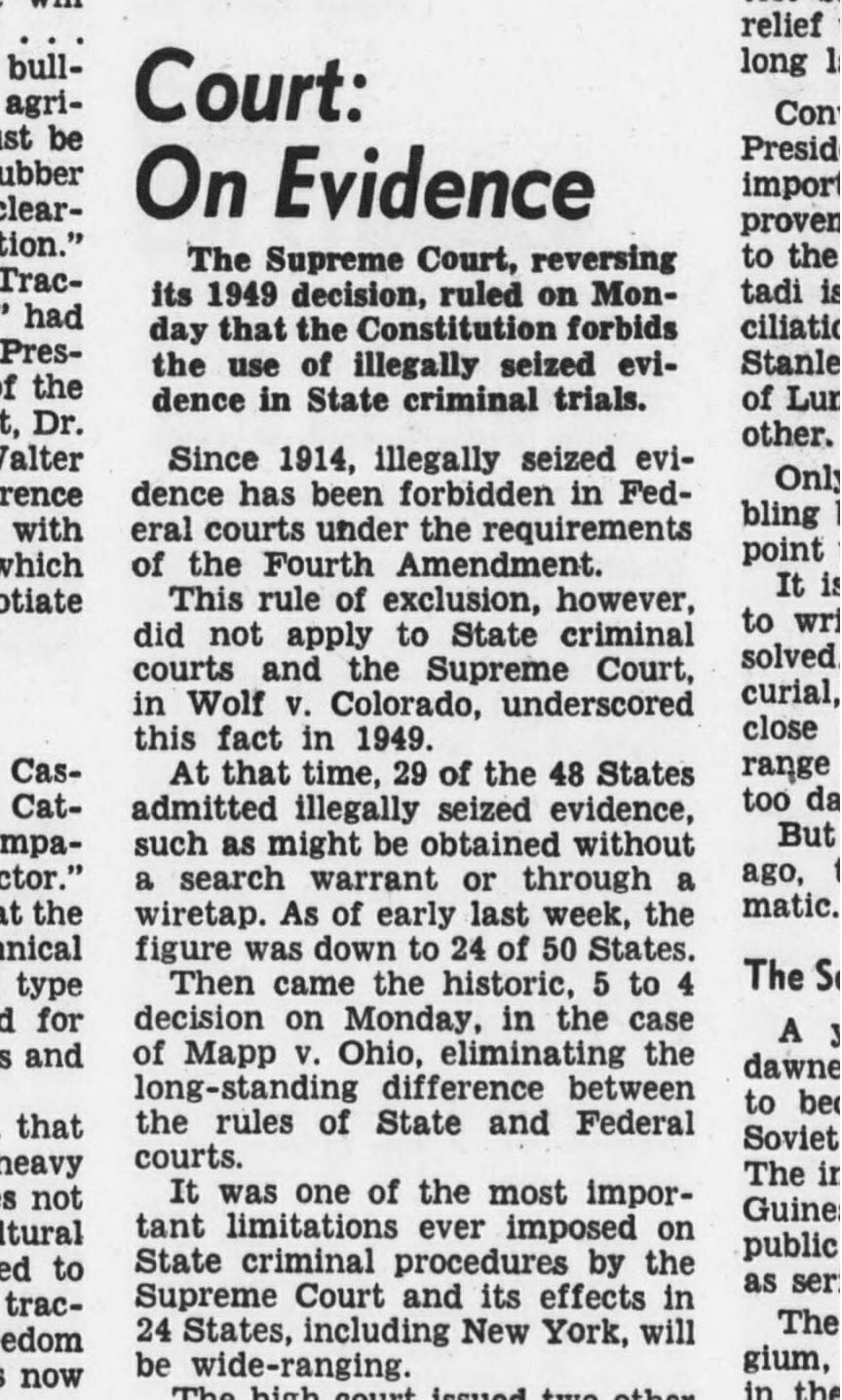

Weeks v. US: exclusionary rule

February 24, 1914

The Supreme Court ruled that if the Fourth Amendment is violated when evidence is seized in a search, that evidence is generally inadmissible at a criminal trial. This is known as the exclusionary rule. The Weeks case took place in federal court, so the ruling only applied to the federal government. In 1961, Mapp v. Ohio extended the exclusionary rule to state governments.

Source: Lexis Nexis

Patton v. US: defendant may forego jury trial

April 14, 1930

The Supreme Court ruled that if a defendant wishes, they can give up their right to a jury trial and have the judge decide their case. In some instances, though, the prosecution and judge must also agree to forego having a jury.

Source: Annenberg Classroom

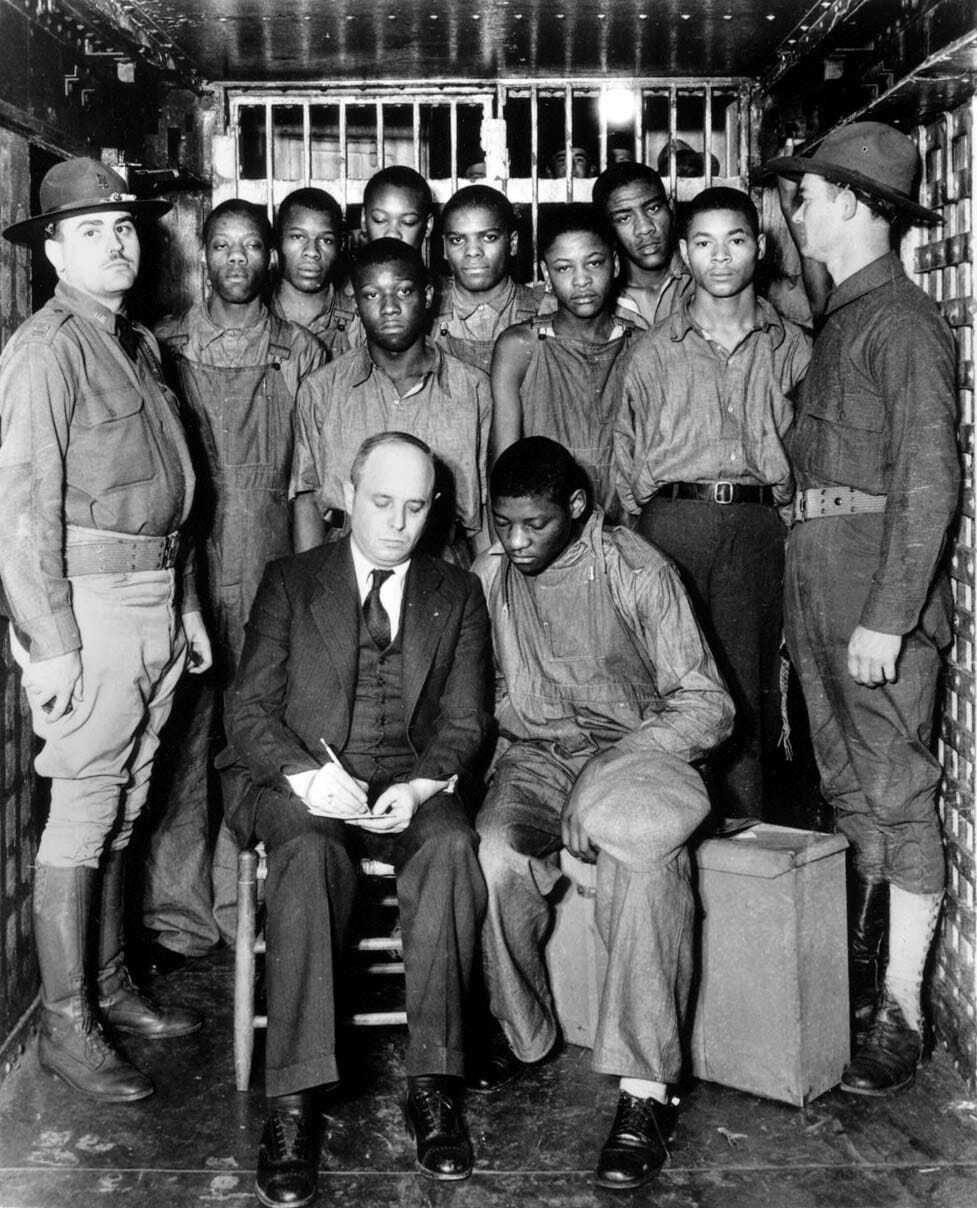

Supreme Court overturned Scottsboro Boys conviction

November 7, 1932

The Supreme Court overturned the convictions of nine African American boys who were tried in Scottsboro, Alabama, for rape and were sentenced to death. The Court ruled that the boys’ attorney did not have the time nor information to properly defend the boys in court. Another Supreme Court hearing found that the boys’ trials had excluded African Americans from serving on the jury and ordered the trials to be reheard with new juries.

Source: Annenberg Classroom

Related Inquiry Packs:

Norris v. AL: all-White juries unconstitutional

April 1, 1935

Excluding Black people from juries was a common strategy in the South. The jury in the Scottsboro Boys’ trial was all White. This Supreme Court case, named after Clarence Norris, one of the nine Scottsboro Boys, challenged the constitutionality of all-White juries. Though Alabama law at the time did not prohibit Black people from serving on juries, they were often intentionally excluded. The Court ruled that this practice was discriminatory based on the disproportionate number of African Americans who lived in Scottsboro and the number of African Americans who served on juries. As a result of this case, Norris’ conviction was overturned. He was tried a third time in 1937 and sentenced to death.

Source: Legal Information Institute (Cornell Law School)

Related Inquiry Packs:

“How a 1944 Supreme Court Ruling on Internment Camps Led to a Reckoning,” Retro Report, Oct 18, 2022, https://youtu.be/4foV5qAnFzs.

Korematsu v. US: individual rights can be denied to protect country

December 18, 1944

After Pearl Harbor was bombed in December 1941, the military feared a Japanese attack on the U.S. mainland. The government worried that Americans of Japanese descent might aid the enemy. In 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed an executive order forcing many people of Japanese descent living on the West Coast to leave their homes and businesses and relocate to internment camps for the duration of the war. Fred Korematsu, an American citizen of Japanese descent, was arrested and convicted of violating the executive order. Korematsu challenged his conviction in court arguing that the government did not have the power to force people to relocate to camps and that he was being discriminated against based on his race. The government argued that the evacuation was necessary to protect national security.

Korematsu’s case eventually made it to the Supreme Court. The Court agreed with the government and stated that the need to protect the country was a greater priority than the individual rights of the people of Japanese descent forced into internment camps.

(Many people considered this decision to be a stain on the Court's legitimacy. Congress later passed a bill providing compensation for victims of this discrimination.)

Source: LandmarkCases.org

Hernandez v. TX: Mexican Americans cannot be excluded from juries

May 3, 1954

Pete Hernandez was a Mexican American cotton picker accused of murder in Texas. Though his town was 14% Mexican American, no Mexican Americans served on his jury. Hernandez sued, arguing this violated his Sixth Amendment right to a fair jury and the Due Process Clause of the 14th Amendment. The Supreme Court agreed. It ruled that the exclusion of Mexican Americans from the jury violated the 14th Amendment’s Due Process Clause and prevented Hernandez from getting a fair trial.

Source: Library of Congress

Trop v. Dulles: revoking citizenship violates 8th Amendment

March 31, 1958

In this case the Supreme Court ruled that punishing a natural-born citizen by revoking their citizenship is cruel and unusual punishment. It also stated that the interpretation of the Eighth Amendment “must draw its meaning from the evolving standards of decency that mark the progress of a maturing society.”

Source: Oyez

Mapp v. OH: exclusionary rule applies to states

June 19, 1961

Suspicious that Dollree Mapp might be hiding a person suspected in a bombing, the police demanded entrance into her home. Mapp refused to let them in because they did not have a warrant. The police returned later and forced their way into her house. They held up a piece of paper, but when Mapp demanded to see their search warrant, they would not show it to her. As a result of their search, the police found a trunk containing pornographic materials, which were illegal to possess at that time. They arrested Mapp and charged her with violating an Ohio law against the possession of obscene materials. She was found guilty in court and sentenced to jail.

After losing an appeal to the Ohio Supreme Court, Mapp took her case to the U.S. Supreme Court. The Court used the incorporation doctrine to apply the decision in Weeks v. United States (1914), which established the exclusionary rule, to the states. It determined that evidence obtained through a search that violates the Fourth Amendment is inadmissible in state courts.

Source: LandmarkCases.org

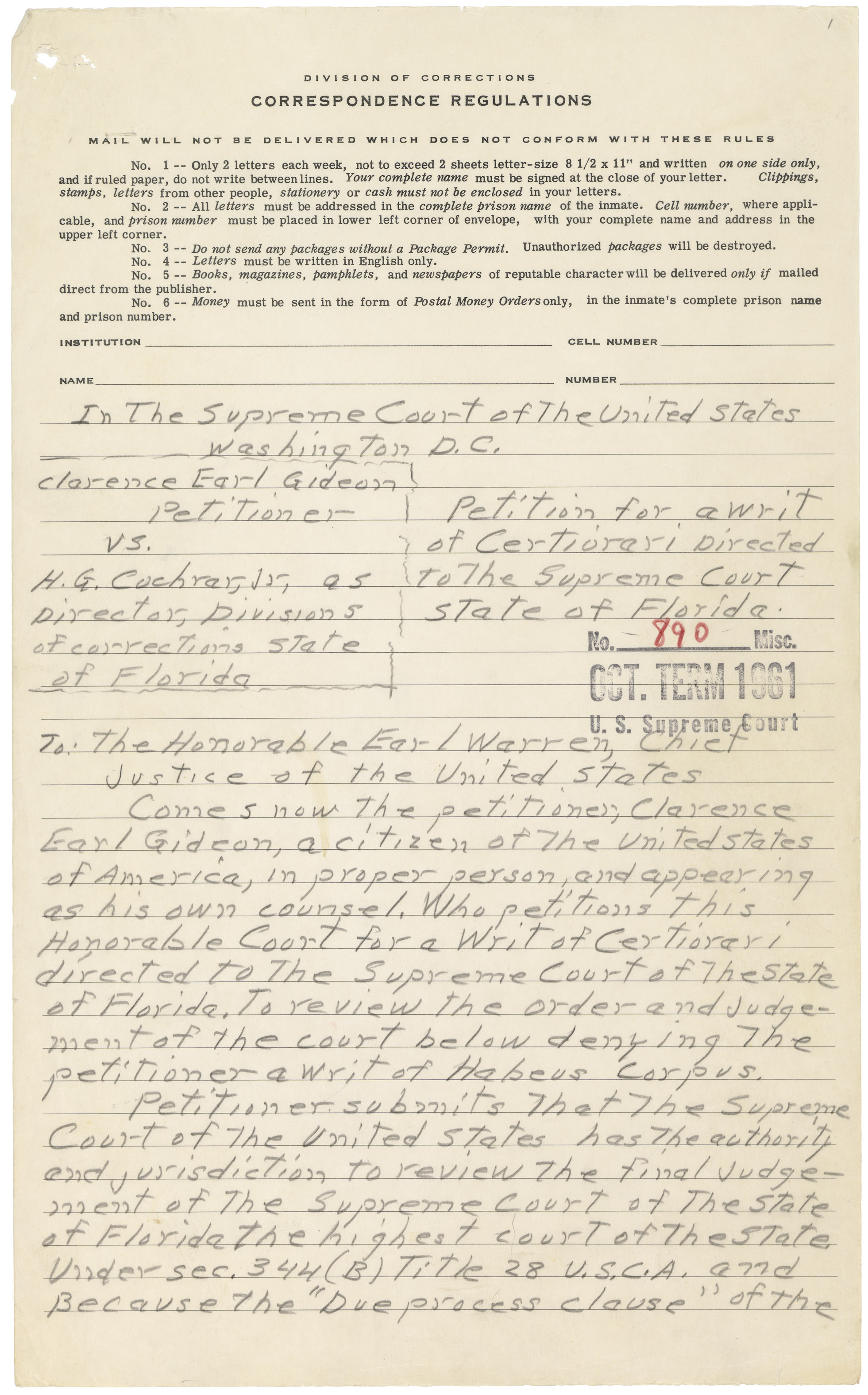

Gideon v. Wainwright: right to counsel applies to states

March 18, 1963

Many states and the federal government required attorneys to be assigned to defendants in felony (serious crimes) cases if they could not afford them. However, it was not until the decision in Gideon v. Wainwright that the Supreme Court used the incorporation doctrine to require states to provide attorneys to defendants accused of felonies.

Source: Annenberg Classroom

Related Inquiry Packs:

Miranda v. AZ: people in custody must be informed of rights

June 13, 1966

The Supreme Court ruled that when a person is taken into police custody and questioned, they must be informed of their right to protection against self-incrimination and the right to a lawyer. As a result of this case, law enforcement must tell a person who is in custody and being interrogated (questioned) that they have the right to remain silent and the right to an attorney. This statement from police is known as a Miranda warning.

Source: Annenberg Classroom

Related Inquiry Packs:

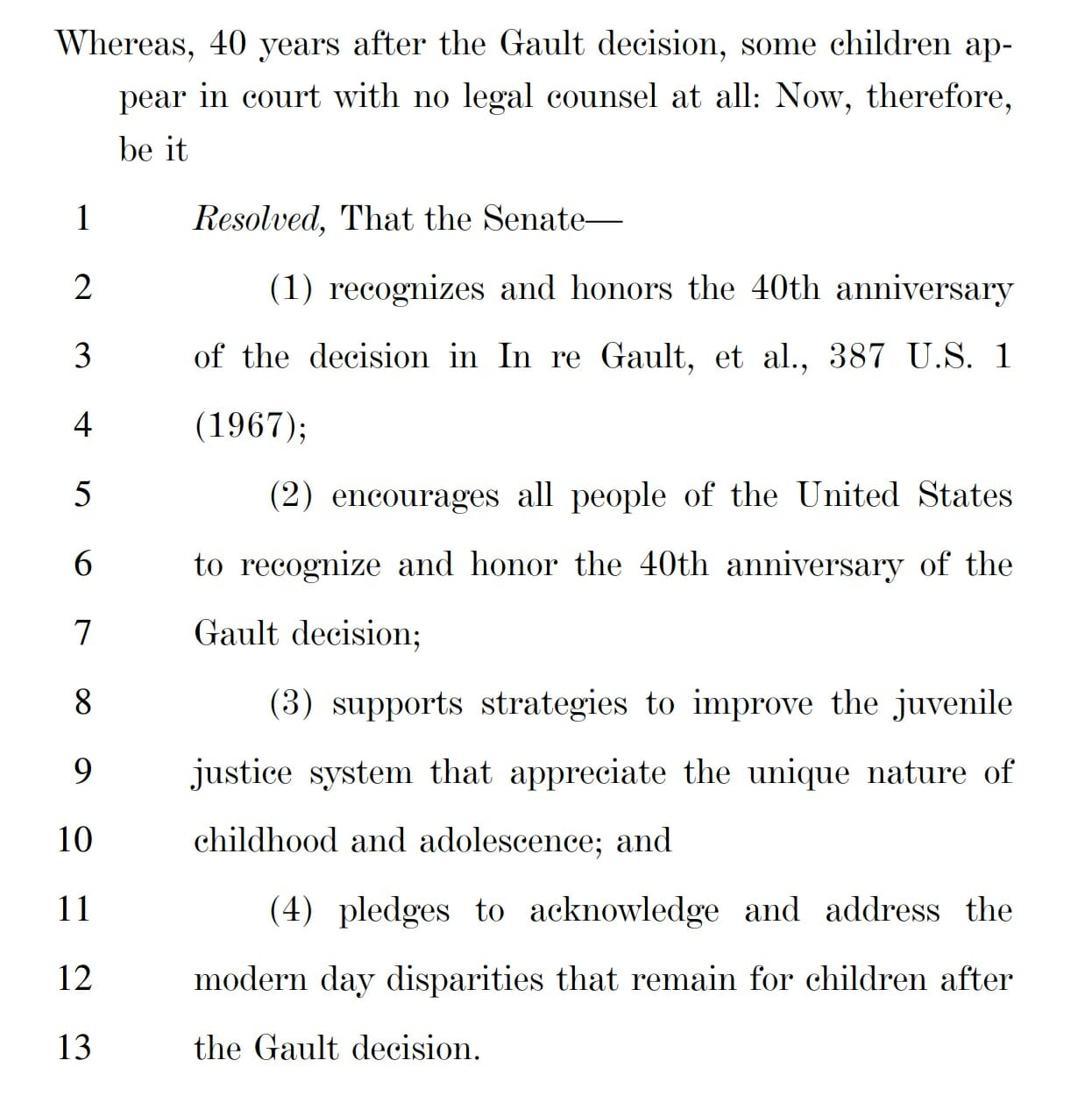

In re Gault: rights apply to youth in juvenile justice system

May 15, 1967

After hearing the case of Gerry Gault, a 15-year-old who was taken into custody by the police for making obscene phone calls, the Supreme Court ruled that youth in the juvenile justice system should be guaranteed several rights granted by the Constitution. These rights include the right to notice of charges, the right to counsel (a lawyer), the right to confront and cross examine witnesses, and the privilege against self-incrimination.

Source: Street Law’s Legal Life Skills Lessons

Related Inquiry Packs:

Katz v. US: “reasonable expectation of privacy”

December 18, 1967

In a case involving law enforcement eavesdropping on telephone calls, the Supreme Court ruled that Fourth Amendment protections apply to individuals as well as physical locations. They stated that not only were people protected in their “persons, houses, papers, and effects” as written in the Fourth Amendment, they were also protected in all places where they had a “reasonable expectation of privacy.”

Source: Oyez

Related Inquiry Packs:

Terry v. OH: stop and frisk is constitutional

June 10, 1968

After observing suspicious behavior, officers stopped and frisked three men without a warrant or probable cause. They found a gun on Terry, and he was convicted of carrying a concealed weapon. He challenged the search of his person and seizure of the gun as a violation of his Fourth Amendment rights.

The Supreme Court ruled for Ohio that the search was reasonable, and the gun could be used as evidence at trial. In its decision the Court noted that the search was reasonable because the officer had more than a hunch and because such searches are meant to protect the safety of the officers.

Source: Oyez

Related Inquiry Packs:

McKeiver v. PA: juveniles do not have right to jury trials

June 21, 1971

The Court ruled that juvenile offenders do not have the same right to a jury trial as adult offenders. This only applies to juveniles tried in a juvenile court.

Source: Annenberg Classroom

Related Inquiry Packs:

Furman v. GA: death penalty is unconstitutional

June 29, 1972

In this Eighth Amendment case, the Supreme Court ruled that most death penalty laws and guidelines were unconstitutional because they were unfairly applied. This decision struck down state death penalty use in 41 states. The case spurred 37 states to rewrite their death penalty laws to align to the Supreme Court’s principles. Four years later, in Gregg v. Georgia (1976) the Court changed direction and again allowed capital punishment as long as the death penalty law took into account aggravating and mitigating circumstances.

Source: LandmarkCases.org

Related Inquiry Packs:

"Right to Privacy: New Jersey v. T.L.O.," Civics 101, March 24, 2021, https://youtu.be/0-jlEJXCTfQ.

New Jersey v. TLO: 4th Amendment rights of public school students

January 15, 1985

A New Jersey high school student (known by their initials: T.L.O.) was accused of violating school rules by smoking in the restroom, leading an assistant principal to search her purse for cigarettes. The search revealed marijuana and other items that implicated the student in dealing marijuana, which was illegal. The student tried to have the evidence from her purse excluded from being used at trial, arguing that the search violated her Fourth Amendment rights. The Supreme Court decided that public school administrators can search a student and their belongings if they have a reasonable suspicion of a violation of criminal law or of school rules. This established a more lenient Fourth Amendment standard than probable cause, which governed police searches of individuals outside the public school context.

Source: LandmarkCases.org

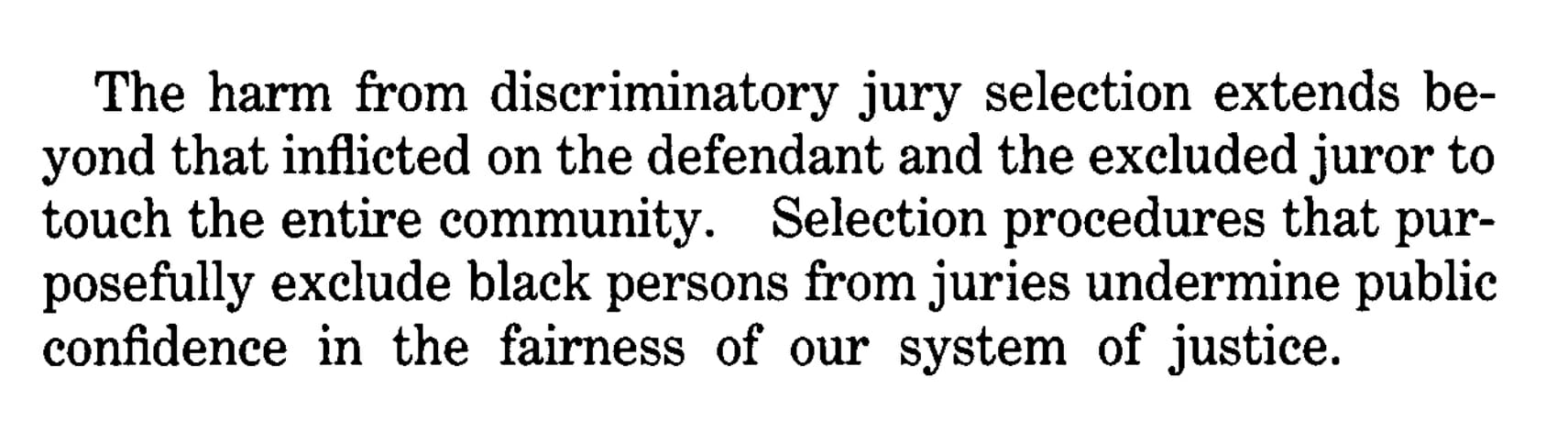

Batson v. KY: potential jurors cannot be excluded based on race

April 30, 1986

James Batson was a Black man convicted of burglary by an all-White jury in Louisville, Kentucky. Although several African Americans were part of the jury pool, they were all dismissed with peremptory challenges. Peremptory challenges are strikes used by lawyers to dismiss some jurors without having to explain the reason. Batson’s lawyer argued that his Sixth and 14th Amendment rights were violated. The Supreme Court ruled that prosecutors cannot use peremptory challenges to exclude people from the jury based on race.

Sources: Legal Information Institute (Cornell Law School) and U.S. Courts.

Department of Justice report finds racial disparities in executions

September 12, 2000

The U.S. Department of Justice reported that over a 12-year period of study federal prosecutors were more likely to seek the death penalty when a racial minority defendant is charged with killing a White person than when they are charged with killing someone who is not White. Under similar circumstances, federal prosecutors are less likely to seek the death penalty for White defendants who charged in the killing of a person from a racial minority group.

Source: Annenberg Classroom

Atkins v. VA: people with intellectual disabilities cannot be sentenced to death

June 20, 2002

The Supreme Court ruled that people who have intellectual disabilities cannot be sentenced to death because it constitutes cruel and unusual punishment. Prior to this decision, many states had already made laws prohibiting the death penalty for people who have intellectual and mental disabilities. The Supreme Court again used the phrase “evolving standards of decency” in its opinion.

Source: Oyez

Crawford v. WA: defendants have right to cross examine witnesses

March 8, 2004

At Crawford’s criminal trial, a tape recording of his wife’s statement was played for the jury. Because it was recorded, his attorney was unable to cross examine her testimony. Earlier Supreme Court precedents allowed certain hearsay (out of court) statements such as this to be used against a defendant at a criminal trial.

In a unanimous opinion, the Supreme Court ruled that the use of a statement given to police before the trial—and where the witness was not available to testify at trial—could not be used against the defendant because of the Sixth Amendment right to confront and cross examine witnesses in criminal cases.

Source: Oyez

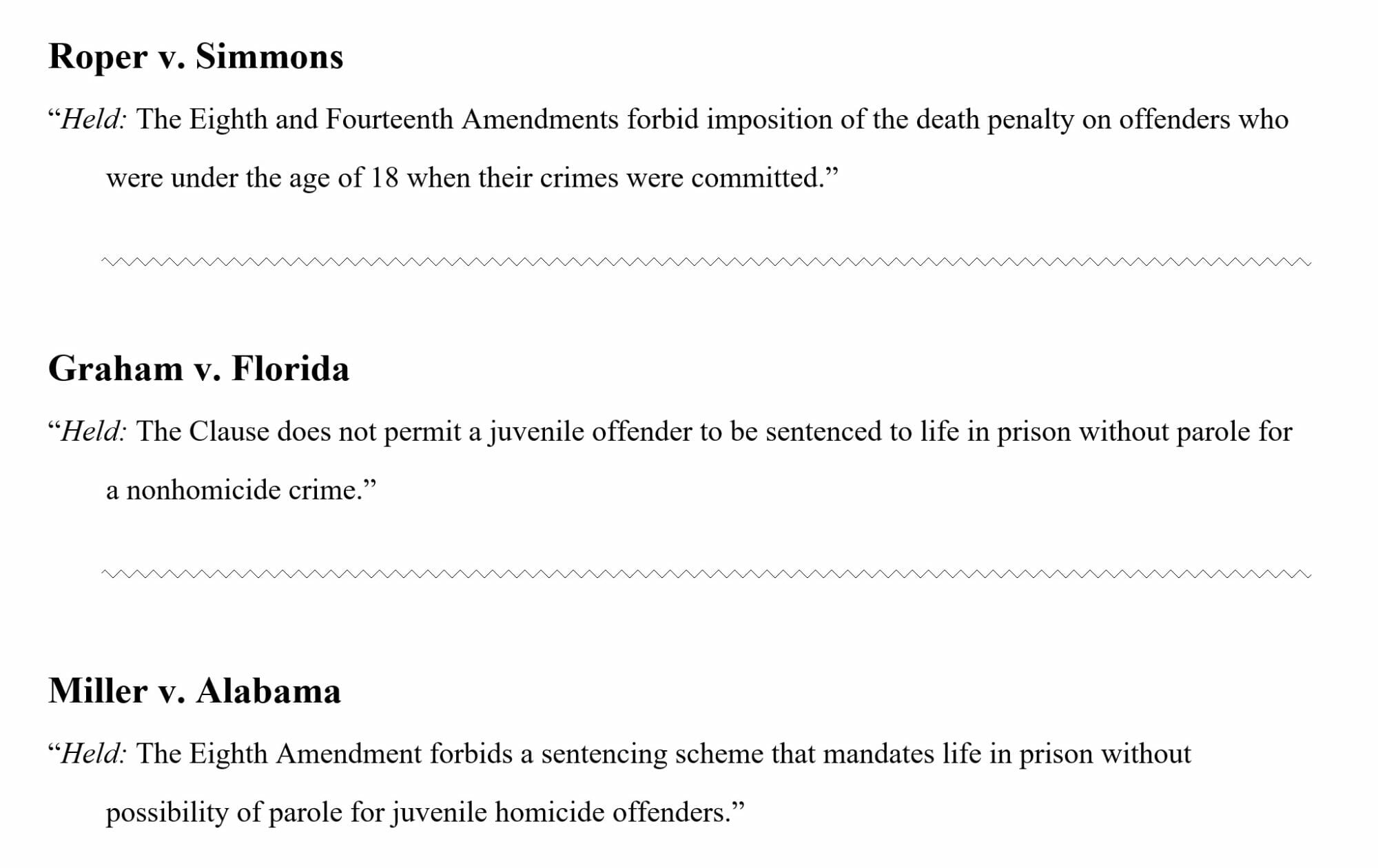

Supreme Court ruled on several cases to limits punishment of minors

2005-2012

During this period, the Supreme Court heard several cases about sentencing minors. In Roper v. Simmons (2005), the Court ruled that people who committed crimes before the age of 18 cannot be executed. In Graham v. Florida (2010), the Court ruled that sentencing a minor to a life sentence without the possibility of parole for any crime other than murder is cruel and unusual punishment. In Miller v. Alabama (2012), the Court ruled that mandatory life sentences without the possibility of parole are unconstitutional for juvenile offenders.

Source: National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers

Related Inquiry Packs:

"DNA Clues Solve Crimes . . . With a Privacy Cost," Retro Report on PBS, October 11, 2019, https://youtu.be/mTlevgsC-YE.

MD v. King: DNA swabs do not require a warrant

June 3, 2013

A Maryland law allowed police to swab suspects of violent crimes for DNA during booking. A man arrested on assault charges appealed arguing that the collection of his DNA was a search that required a warrant. The Supreme Court had to decide if the Fourth Amendment allows states to collect and analyze DNA upon arrest (before conviction).

The Court ruled that DNA swab tests were a routine part of the booking procedure and do not require a warrant. This decision has been applied so that police also do not need a warrant to search for matches in genealogy website databases to which people voluntarily submit their DNA

Source: Retro Report on PBS

Riley v. CA: warrant needed to search a cell phone

June 25, 2014

In a unanimous decision, the Supreme Court ruled that the Fourth Amendment requires that police must usually obtain a search warrant before searching data on a cell phone. The Supreme Court said in its opinion that modern cellphones are “now such a pervasive and insistent part of daily life that the proverbial visitor from Mars might conclude they were an important feature of human anatomy” and that cell phones include information about most aspects of people’s lives. Therefore, to search the enormous amount of data people store on them, police would in most instances be required to get a search warrant.

Source: Oyez

“Legalese: The ‘Third Party Doctrine’ and Carpenter v. United States,” Georgetown Law, June 25, 2018, https://youtu.be/2ZH9Bd-pCrg.

Carpenter v. US: warrant needed to obtain location data

June 22, 2018

The FBI suspected Carpenter in several armed robberies and wanted to review data about the location of his cell phone. A federal law allows law enforcement officers to request an order from a judge that requires a telecommunications company to turn over such records, but this is not a warrant. The government used the location data at Carpenter’s trial, and he was convicted of nine armed robberies. He challenged his convictions because the officers did not have a warrant.

The Supreme Court found in favor of Carpenter. It decided that the collection of his cell-site location information was a search and that he had a reasonable expectation of privacy in his location; therefore, the government needed a warrant to search data that would reveal that information. The Court clarified that although the government would usually need a warrant to search location data, there would be some notable exceptions, most likely for “exigent” or emergency circumstances—for example, to quickly locate an abducted child.

Source: Oyez

Related Inquiry Packs:

Nina Totenberg , “Supreme Court Limits Civil Asset Forfeiture, Rules Excessive Fines Apply To States,” NPR Morning Edition, February 20, 2019, https://www.npr.org/transcripts/696360090.

Timbs v. IN: states cannot impose unreasonable fines

February 20, 2019

Timbs was arrested for selling narcotics, and the state of Indiana seized his Land Rover SUV valued at $42,000. Timbs challenged the seizure arguing that the Supreme Court should use the incorporation doctrine to apply the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition of excessive fines to protect him from Indiana’s seizure. In Tyson Timbs and a 2012 Land Rover v. the State of Indiana, the Supreme Court decided unanimously for Timbs that the Eighth Amendment's Excessive Fines Clause should be applied to the states.

Flowers v. MS: reaffirmed potential jurors cannot be dismissed because of race

June 21, 2019

Flowers, who is African American, was charged with a quadruple homicide (murder). Over time, he was prosecuted six times by the same prosecutor. The first five trials ended in hung juries, mistrials, and overturned convictions. In the sixth trial, Flowers was convicted of four capital murders and sentenced to death by lethal injection.

Throughout the six prosecutions, the constitutionality of the prosecutor’s actions during voir dire (questioning of the jury pool) were questioned as possibly discriminatory. He used 41 of 43 peremptory challenges available to remove African Americans from the jury pool. Flowers appealed his conviction claiming that the strikes in the sixth trial violated Batson v. Kentucky, which ruled that jurors cannot be removed from the pool because of their race.

The Supreme Court found in favor of Flowers citing that the prosecutor’s strike of a particular Black juror was motivated, at least in part, by discriminatory intent. The Court also stated that the prosecutor’s actions in the earlier trials must influence the Court’s understanding of his intent in the sixth trial based on this historical pattern of racial discrimination in jury selection.

Source: Oyez

Related Inquiry Packs: