Timeline Contents

"What is Magna Carta?," British Library, March 10, 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7xo4tUMdAMw

Magna Carta signed: foundation for rule of law and limited rights of king

July 15, 1215

King John of England signed a written charter of rights. This document provided the foundations for much of the U.S. Constitution and Bill of Rights. In the Magna Carta, King John agreed to the principle that kings were not above the law, an important factor of the rule of law.

Sources: British Library and Library of Congress

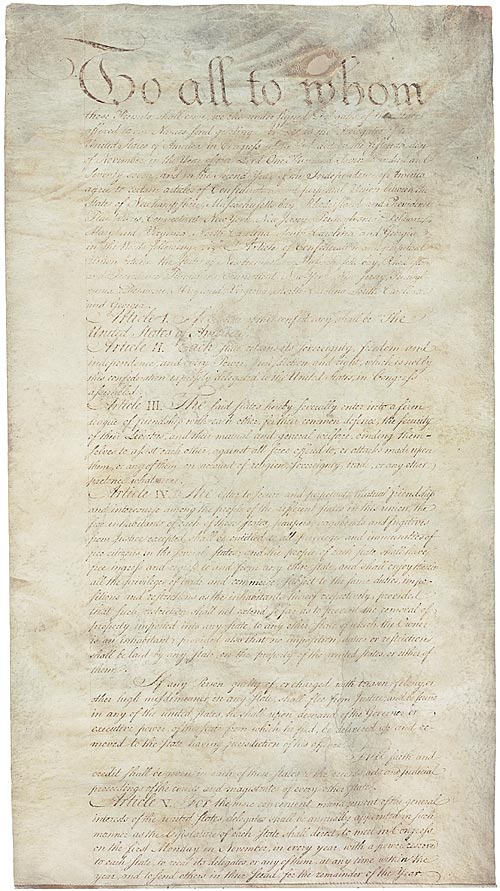

Articles of Confederation: no executive branch

November 15, 1777–September 17, 1787

Many Americans were skeptical of having a president after the harsh reign of England’s King George III. Therefore, America’s first constitution, the Articles of Confederation, had no executive branch or president. All executive functions fell to Congress or the states. This and other weaknesses in the government created by the Articles of Confederation, caused it to be short-lived. It was replaced by the U.S. Constitution in 1787.

Source: National Archives

Constitutional Convention

May 25, 1787 - Sep 17, 1787

The Framers of the Constitution met in Philadelphia and drafted the U.S. Constitution. They considered and debated ideas about the structure of government they learned from Enlightenment thinkers such as Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, Charles Montesquieu, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

The delegates debated whether there should be a unitary (singular) president or a plural executive, the term of office, possible term limits, the powers the president should have including veto power and the power to grant pardons, and the method of election. The Federalists argued for a strong singular president and were ultimately successful.

The delegates to the convention knew George Washington would almost certainly be elected the first president, so in many ways the position was created with him in mind. The delegates hoped that his successors would follow the precedents he would set and not abuse the power entrusted to them by the Constitution.

Source: Constitutional Rights Foundation and Center for the Study of the American Constitution (University of Wisconsin-Madison)

"Formal and informal powers of the US president | US government and civics | Khan Academy," Khan Academy, December 27, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TG63zz1AFjc

U.S. Constitution signed: includes expressed powers in Article 2

September 17, 1787

Article 2 of the U.S. Constitution established the expressed powers of the president. These are the powers that are explicitly written out in the Constitution. The expressed powers include the power to:

- sign or veto legislation

- act as commander-in-chief of the armed forces

- ask for the written opinion of their cabinet

- convene or adjourn Congress

- grant reprieves and pardons

- appoint U.S. ambassadors

- take care that the laws are faithfully executed

- appoint and remove executive officers

- make treaties, which need to be ratified by two-thirds of the Senate

- appoint federal judges including Supreme Court justices and some officers with the advice and consent of the U.S. Senate

Source: Congress.gov

Related Inquiry Packs:

Federalist No. 70: Alexander Hamilton advocated for singular president

March 15, 1788

In Federalist No. 70, Alexander Hamilton made the case for a strong, unitary (singular) president. Many Americans were leery of having one powerful president after the reign of King George III and no executive branch at all under the Articles of Confederation. Hamilton argued that a strong executive like the one created in the Constitution was necessary for the country to survive.

Source: Library of Congress

Washington inaugurated as first president of the United States

April 30, 1789

In 1789, George Washington was unanimously elected by the Electoral College to be the first president of the United States for which among other accomplishments he earned the name, “Father of His Country.” President Washington did not have any role model to base his actions on. Every decision he made set a precedent for presidents to come.

Source: Mount Vernon

First executive order issued by Pres. Washington

June 8, 1789

On June 8, 1789, President George Washington issued the first executive order. The order directed John Jay, Secretary of Foreign Affairs under the Articles of Confederation, to provide “a clear account of the Department at the head of which you have been, as may be sufficient … to impress me with a full, precise and distinct general idea of the United States.”

Washington issued seven additional proclamations or orders during his eight years as president, including the proclamation declaring a day of thanksgiving on November 26, 1789.

Source: Governing

Related Inquiry Packs:

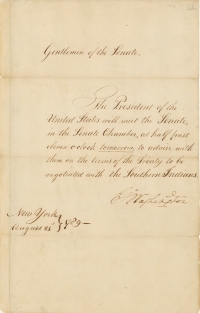

Senate’s advice on treaty requested by Pres. Washington

August 21, 1789

The Framers decided that treatymaking would be a power shared between the president and the Senate. Article 2, Section 2 of the U.S. Constitution states that the president “shall have Power, by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, to make Treaties, provided two-thirds of the Senators present concur.” But further details about how the “advice” and “consent” would take place were not given.

In August 1789, President George Washington sought the Senate’s advice on a treaty with Native Americans. He wrote to the Senate requesting a meeting. He noted that the “inclination or ideas of different Presidents may be different” predicting that in the future the Senate would need to be flexible in the process by which it provides its advice and consent. The Senate committee agreed with the president “that the opinions both of the President and the Senate as to the proper manner may be changed by experience.”

The Senate provided for the president to meet with them in the Senate chamber. On the same day, President Washington’s secretary delivered a message stating the president would meet with senators the following day “to advise with them on the terms of the Treaty to be negotiated with the Southern Indians.”

Source: United States Senate

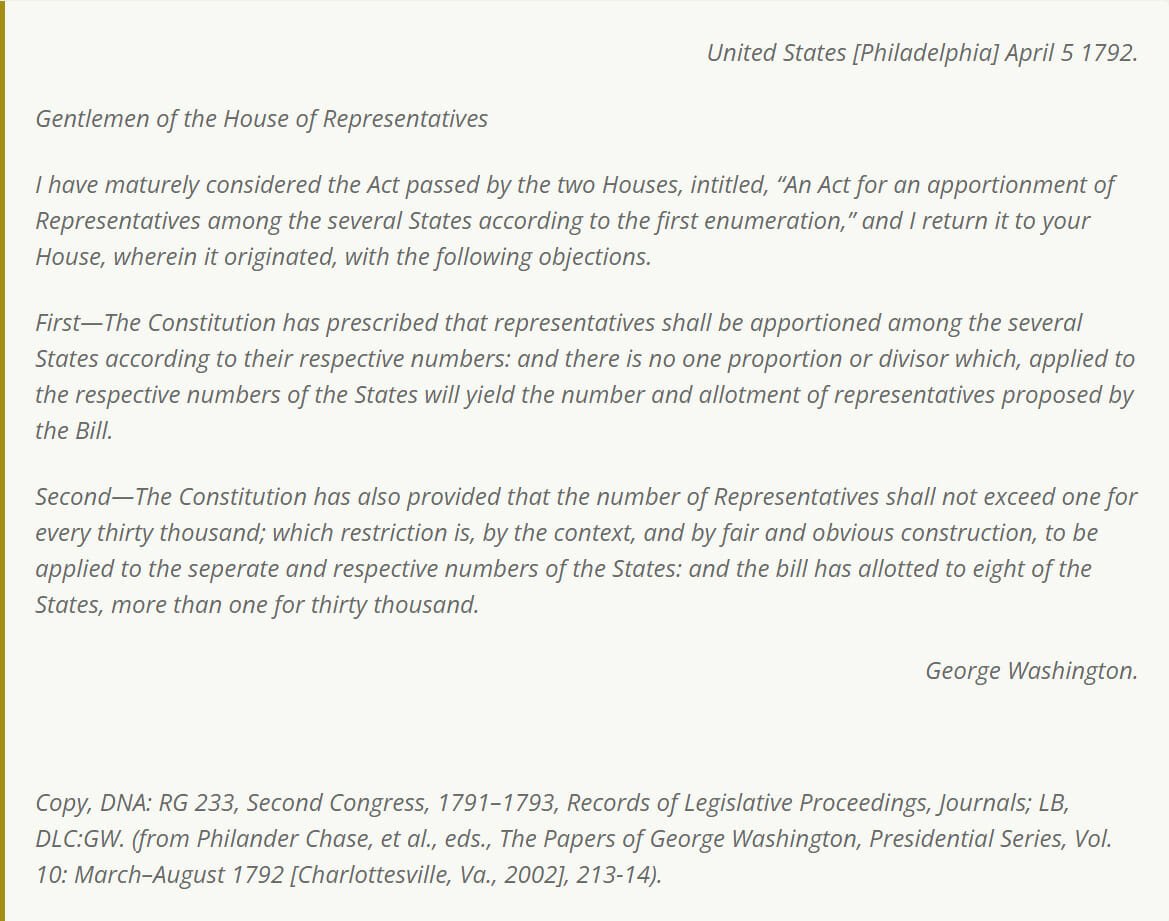

First presidential veto

April 5, 1792

On April 5, 1792, President George Washington exercised the first presidential veto. The bill introduced a new plan for dividing seats in the House of Representatives. After consulting with his cabinet, President Washington decided that the plan was unconstitutional because it would have increased the number of representatives, thereby exceeding the number set by the Constitution. He argued that the law had unfairly “allotted to eight of the States, more than one [representative] for thirty thousand,”* potentially creating an imbalance in power.

President Washington only used his veto power one other time during his two terms in office. In February 1797, he vetoed an act that would have reduced the size and cost of the army by eliminating two cavalry units. In both instances, Congress was unable to override the veto.

Sources: History.com and *Mount Vernon

Related Inquiry Packs:

Executive privilege invoked by Pres. Washington

March 30, 1796

In 1792, the House of Representatives formed a committee to investigate a failed military expedition. The committee asked President Washington to turn over papers and records to aid their investigation. Since this was the first request of its kind, President Washington held a meeting of his cabinet to discuss what he should do. The cabinet and the president decided they should explain to Congress that “the Executive ought to communicate such papers as the public good would permit, and ought to refuse those, the disclosure of which would injure the public.” In this case, they felt the requested papers were appropriate, so they provided them to the committee.

Then, in 1796, the House of Representatives requested documents from the president to inform an investigation regarding the Jay Treaty, which had been signed recently between the United States and Great Britain. This time President Washington refused to turn over the information. He argued that the Constitution tasks the Senate, not the House, with giving “advice and consent” regarding treaties.

Later, the Senate requested all correspondence from officials involved in negotiating the Jay Treaty. President Washington eventually provided the correspondence but with some information redacted (blacked out). President Washington told Congress that the circumstances “forbid a compliance with your request” because of the need for diplomacy, secrecy, and caution in foreign relations.

This was one of the first uses of what would later be called executive privilege. Executive privilege is the withholding of information by the president from the courts, Congress, or the public. No mention of executive privilege is written in the Constitution.

Sources: U.S. Department of Justice, and The Washington Post

Related Inquiry Packs:

Neutrality proclamation issued by Pres. Washington

April 22, 1793

In 1793, George Washington issued a neutrality proclamation calling for the United States to stay neutral in a European conflict during the French Revolution. The neutrality proclamation warned Americans that the federal government would prosecute citizens for aiding either side of the conflict.

Opponents questioned whether the president had the authority to issue such a proclamation because this power was not explicitly included in Article 2 of the U.S. Constitution. Supporters felt the neutrality proclamation was part of the president’s inherent powers. The question of the president’s authority was never resolved, however, because in 1794, the Neutrality Act was passed by Congress giving the order the force of law.

Source: Mount Vernon

First presidential pardon granted by Pres. Washington

November 2, 1795

President George Washington first exercised the pardon power in 1795, after he issued amnesty to men charged for treason for their part in the Whiskey Rebellion. The power to pardon is an expressed power of the president found in Article 2 of the U.S. Constitution.

Source: Smithsonian Magazine and White House Historical Association

Related Inquiry Packs:

Pres. Washington’s Farewell Address

September 19, 1796

Despite many calls to run for a third term, President George Washington chose not to seek re-election. He knew that his conduct would set the precedent for future presidents and feared that if he were to die while in office, the presidency would be thought of as a lifetime appointment.

President Washington decided to step down from power, setting the precedent of a two-term limit. Only one president, Franklin Roosevelt, would break with that precedent that was added to the Constitution in 1951 with the ratification of the 22nd Amendment.

At the end of his second term, President Washington drafted a Farewell Address with the help of James Madison and Alexander Hamilton. He began the address by explaining his choice not to seek a third term as president and assuring the country that his leadership was no longer needed.

President Washington also stressed that to safeguard their hard-won system of republican government, the country had to remain united. He cautioned against regional loyalties, partisanship, and foreign entanglements. Washington concluded his address with the hope that his legacy would be viewed kindly.

Today, President Washington’s Farewell Address is considered a founding document cautioning against partisanship and advocating for unity.

Source: Mount Vernon

Related Inquiry Packs:

"Marbury vs. Madison: What Was the Case About? | History," September 14, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hOvsZyqRfCo

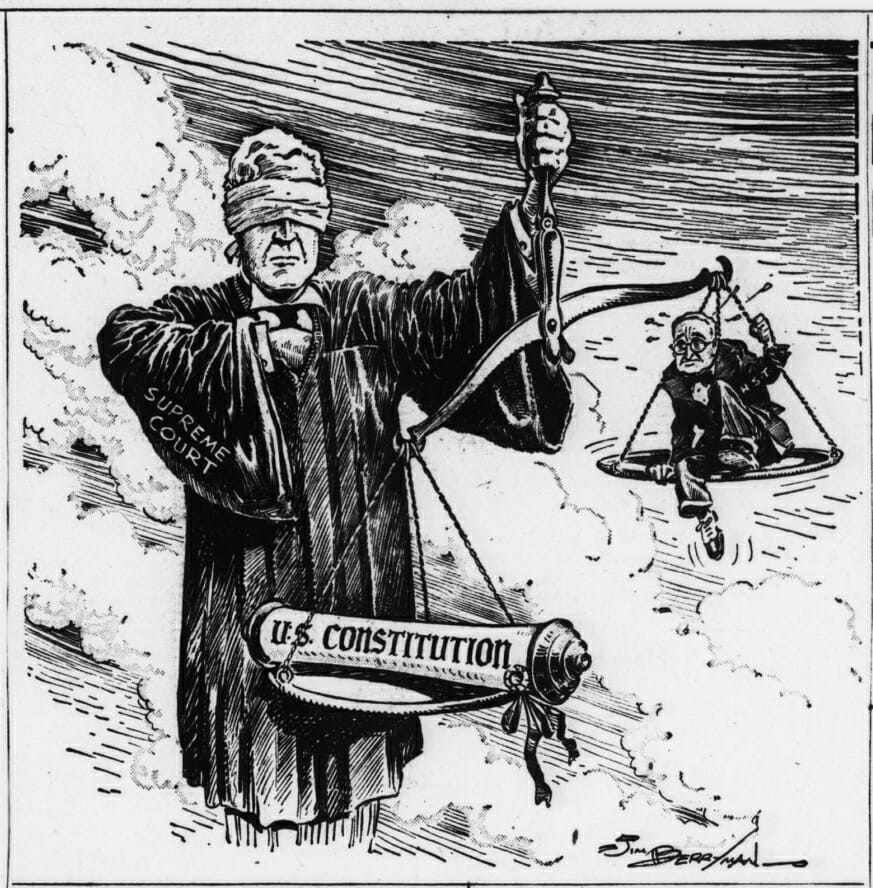

Marbury v. Madison: judicial review

February 24, 1803

The decision in Marbury v. Madison established judicial review, one of the most significant principles of American constitutional law. In this case the Supreme Court ruled that it is the Court itself that has the final say on what the Constitution means. The Supreme Court also has the final say in whether an act of government—legislative or executive at the federal, state, or local level—violates the Constitution. This ruling made clear that the Supreme Court could also declare a presidential act unconstitutional.

Source: Congress.gov and United States Government: Our Democracy (McGraw Hill Education)

Little v. Barreme: judicial review used to declare a presidential action unconstitutional

December 8, 1804

President John Adams issued an order to the Navy to stop any American ship suspected of breaking an embargo on France by traveling to or from French-controlled ports. Subsequently, a Danish vessel, the Flying-Fish, was mistaken for an American ship and seized by the Navy after it was spotted leaving a French-controlled port.

The question of the legality of the seizure went to the U.S. Supreme Court: Did the president have the authority to issue the order to capture ships traveling from French ports?

The Supreme Court decided that President Adams did not have “any special authority” to order the seizure of ships departing French ports. Even if the Flying-Fish had been an American ship, it still would not have been within the president’s power to order its seizure.

Source: Oyez

Louisiana Purchase initiated by Pres. Jefferson

1803-1804

The Louisiana Purchase was a deal between France and the United States for the purchase of approximately 827,000 square miles of territory west of the Mississippi River in exchange for $15 million. France, fearing war in the territory and not in a position to defend it, agreed to sell the land to the United States.

President Jefferson and his cabinet deliberated the constitutionality of the purchase. President Jefferson suggested an amendment to the Constitution was needed.

President Jefferson drafted an amendment that would authorize the purchase of Louisiana retroactively, but his cabinet tried to convince him otherwise. In the end, the president accepted his cabinet’s advice that an amendment was not necessary.

The Senate ratified the purchase treaty on October 20, 1803, by a vote of 24 to 7. The United States took formal possession on December 30, 1803.

Some historians have argued that President Jefferson acted hypocritically because the power to purchase the land was not explicitly written in the Constitution, which he usually believed was necessary for the government to act. They accuse him of stretching the intent of the Constitution to justify his purchase. Many people believe that he did something that he would have likely argued against if it had been done by Alexander Hamilton and the Federalists, his political rivals.

Sources: Bill of Rights Institute, Monticello, and The Writings of Thomas Jefferson (collected and edited by Paul Leicester Ford)

Related Inquiry Packs:

![001dr.jpg Cherokee agency, “Orders No. [25] Head Quarters, Eastern Division Cherokee Agency, Ten. May 17, 1838. [n. p. 1838],” Broadside. Library of Congress Rare Book and Special Collections Division, https://www.loc.gov/item/rbpe.1740400a/.](https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/rbc/rbpe/rbpe17/rbpe174/1740400a/001dr.jpg)

Indian Removal Act signed into law by Pres. Jackson

May 28, 1830

In 1830, President Andrew Jackson convinced Congress to pass a bill empowering him to grant Native Americans land west of the Mississippi River in exchange for current tribal holdings within state borders. President Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act into law on May 28, 1830. It was the only major piece of legislation passed at Jackson’s urging in his eight years as president.

Source: Library of Congress

Trail of Tears

1831-1850

President Andrew Jackson used the Indian Removal Act to force Native Americans off their land. Many tribes resisted relocation. In the winter of 1831, members of the Choctaw Nation became the first to endure the forced march to new lands. Thousands died prompting a Choctaw leader to describe it as a “trail of tears and death.”*

Source: *History.com

Worcester v. Georgia: Native American tribes found sovereign, but Pres. Jackson doesn’t enforce

March 3, 1832

In the 1832 case of Worcester v. Georgia, the U.S. Supreme Court recognized the sovereignty of the Cherokee Nation. The majority opinion was written by Chief Justice John Marshall who pointed to treaties that showed that Native American communities were separate from the states. Chief Justice Marshall wrote that Native Americans “had always been considered as distinct, independent political communities.” This statement declared that Native American tribes had sovereignty and were not subject to the laws of states.

Even though the Supreme Court recognized the sovereignty of the Cherokees, the state of Georgia asked the federal government to push the Cherokees off their territory.

At first, President Andrew Jackson ignored the Supreme Court’s decision. This action, however, threatened to intensify an existing conflict between the federal government and the state of Georgia. Ultimately, there was a compromise that resulted in the law that led to Worcester’s arrest being repealed by the state. Jackson, however, continued to focus his efforts on Indian removal.

Sources: Worcester v. Georgia: Case Pack for Middle School and *History.com

Pres. Jackson’s “Imperial Presidency”

1829-1837

Critics of President Andrew Jackson portrayed him as King Andrew I and coined the term “imperial presidency” to describe his style of leadership. Unlike previous presidents, President Jackson used his veto power and his role as party leader to assume command. He did not defer to Congress in making policy like many of his predecessors.

Source: The White House

Habeas corpus suspended by Pres. Lincoln; Ex parte Merryman case

April–June 1861

On April 27, 1861, during the Civil War and while Congress was in recess, President Abraham Lincoln exercised his commander-in-chief powers to suspend the writ of habeas corpus. Under this order, commanders could arrest without cause and detain individuals who were deemed threatening to military operations without formal charges or a trial. This gave military authorities between Washington, DC, and Philadelphia the necessary power to silence dissenters and rebels.

President Lincoln’s power to suspend habeas corpus was questioned because the Constitution states, “The Privilege of the Writ of Habeas Corpus shall not be suspended, unless when in Cases of Rebellion or Invasion the public Safety may require it.” This clause is found in Article 1 of the U.S. Constitution, which details the powers given and denied to Congress, not Article 2 that lays out the powers of the president.

The constitutionality of President Lincoln’s actions was challenged in the Ex parte Merryman case. When John Merryman, an officer of the Maryland militia, was arrested without being formally charged, he took his case to Chief Justice Roger Taney—where it was decided on June 1, 1861 that President Lincoln did not have power to suspend habeas corpus. The chief justice wrote: “This article is devoted to the Legislative Department of the United States, and has not the slightest reference to the Executive Department.”*

President Lincoln ignored the ruling.

Suggested Resource: Ex parte Merryman: Case Pack for Middle School

Sources: Congress.gov and *A Commentary on the Constitution of the United States (Bernard Schwartz)

Related Inquiry Packs:

![001r.jpg Abraham Lincoln, “Proclamation of emancipation by the President of the United States of America, [Russell],” Broadside, 1868. Library of Congress Rare Book and Special Collections Division, https://www.loc.gov/resource/lprbscsm.scsm0902/.](https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/rbc/lprbscsm/scsm0902/001r.jpg)

Emancipation Proclamation issued by Pres. Lincoln

January 1, 1863

President Abraham Lincoln did not initially think it was constitutional for him to issue an emancipation proclamation. In March 1861, while on the campaign trail then-candidate Lincoln said, “I have no purpose, directly or indirectly to interfere with the institution of slavery in the states where it exists. I believe I have no lawful right to do so, and I have no inclination to do so.”*

However, after the Battle of Antietam during the Civil War, President Lincoln changed his position and argued that his commander-in-chief power gave him authority to issue the Emancipation Proclamation because it was necessary to win the war. The proclamation declared that all enslaved people within rebellious areas were free and also made known that Black men were permitted to join the Union Army and Navy. By issuing the Emancipation Proclamation, President Lincoln hoped to inspire enslaved persons in the Confederacy and abolitionists who opposed slavery to support the Union cause and help win the war.

Sources: *Avalon Project (Yale Law School), Library of Congress, and National Archives

Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act: merit-based system for executive branch employees

January 16, 1883

The term the “spoils system” comes from the saying, “to the victor go the spoils.” It referred to the power of the president to appoint friends and supporters to important positions within the executive department of the federal government. While all presidents used the spoils system to some extent, President Andrew Jackson (president from 1829–1837) was the most notorious and is the president most associated with the term.

President James Garfield was assassinated in 1881 by a person who was angry because he did not receive the federal job he was seeking. After the assassination, Senator George Pendleton (D-Ohio) proposed a law to replace the spoils system with a process that would award federal government jobs based on merit through a competitive process including exams. The Pendleton Act also made it unlawful to demote or fire federal workers for political reasons, forbade requiring workers to perform service or give political contributions, and established the Civil Service Commission to enforce the act. This law made it illegal for presidents to use the federal bureaucracy to aid in their re-election or other political campaigns.

Some jobs within the federal government are still political appointments made at the discretion of the president. However, today the Pendleton Act applies to the vast majority of positions in the federal workforce.

Source: National Archives

“Bully pulpit” coined by Pres. Theodore Roosevelt

February 27, 1909

On February 27, 1909, The Outlook magazine published the following quote by President Theodore Roosevelt, “I suppose my critics will call that preaching, but I have got such a bully pulpit!”*

President Theodore Roosevelt often used the word “bully” to mean wonderful or excellent. A “pulpit” is a place from which religious leaders preach. This term has come to mean a position of authority from which a person has the opportunity to speak out and be listened to on any matter.

Presidents are able to attract a crowd or media attention whenever they wish to speak giving them the important informal power of the bully pulpit. Presidents before and after President Roosevelt coined this term have used the power of the bully pulpit to garner public support for their agendas.

The power of the bully pulpit is an example of an informal power of the presidency—one that is not explicitly written in the Constitution but has developed over time.

Sources: *The Outlook and Political Dictionary

Budget and Accounting Act of 1921

June 10, 1921

The Budget and Accounting Act of 1921 was signed into law by President Warren G. Harding. The act gave the president an advantage in the budget process of being the person who first creates and proposes the annual budget for the U.S. government. Before this act, Congress created the budget and then sent it to the president to sign. With the passage of this act, Congress delegated significant authority to the president making him the chief budget agenda setter.

The act also created the first staff at the disposal of a president to help formulate the annual budget. At the time of the act’s passage, the staff was called the Bureau of the Budget but was later renamed to its current name, the Office of Management and Budget.

Source: University of Central Florida

"What is Veto Power?," History, December 8, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n_3cBWrC5n8

Pocket Veto Case: “adjournment” defined

May 27, 1929

Article 1, Section 7, Clause 2 of the U.S. Constitution established a procedure known as a “pocket veto.” It states that if Congress sends legislation to the president for signature but adjourns within 10 days (not including Sundays) of doing so, the president can ignore the bill and it will not become law. The president’s decision not to sign the legislation is called a pocket veto, and Congress does not have the opportunity to override it. If Congress remains in session and the 10 days elapse, the bill becomes law without the president’s signature.

The Pocket Veto Case involved a bill that authorized some Native American tribes to sue the U.S. Government. The bill passed both the Senate and the House of Representatives. It was then presented to President Calvin Coolidge for his signature on June 24, 1926. On July 3, 1926, the House of Representatives adjourned without a specific date to return, and the Senate also adjourned until November 12. These were the final adjournments of the first session of the 69th Congress (each Congress is two years long; each session is one year long).

The 10-day period provided for presidential action in the Constitution expired on July 6, 1926, three days after the first session of the 69th Congress adjourned. President Coolidge intended to use the pocket veto—neither signing the bill nor returning it to the Senate. The bill was not published as a law.

The tribes filed suit in the Court of Claims arguing that the bill had become a law without the president’s signature because only the first session of the 69th Congress had adjourned. The question in this case focused on the definition of “adjourn.” The tribes argued it meant adjournment of the Congress at the end of two years. The United States contended it meant any time the Congress had adjourned its meeting, including in between sessions.

The Supreme Court found for the United States and upheld the practice of the pocket veto by ruling that a bill that was passed within the last 10 days of a session never became a law because the president did not sign it before Congress adjourned. The Supreme Court’s opinion concluded that the word “adjournment” was not limited to final adjournments of a two-year Congress, but also included interim adjournments between or within sessions.

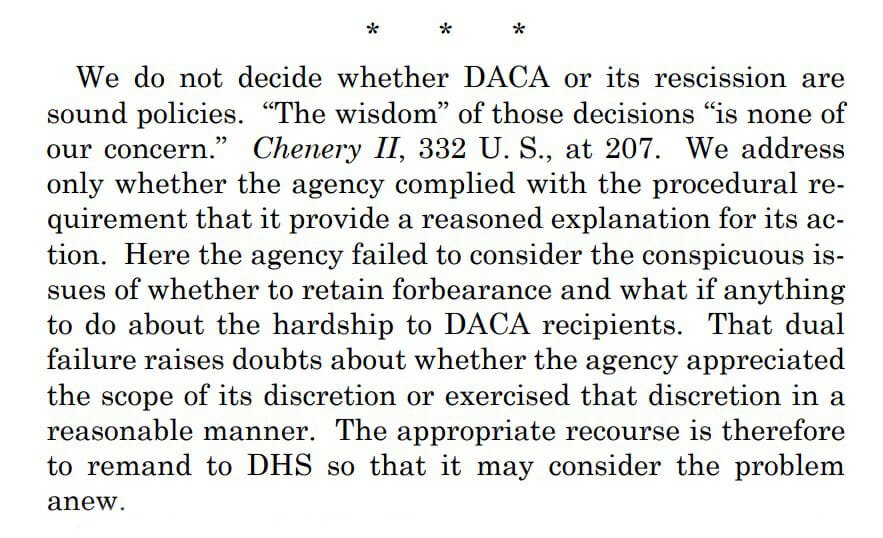

![47304v.jpg "Harris & Ewing, “FDR [Franklin Delano Roosevelt] FIRESIDE CHAT ON U.S. SUPREME COURT REFORM PLAN,” Photograph, 1937. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, https://www.loc.gov/resource/hec.47304/. "](https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/pnp/hec/47300/47304v.jpg)

Fireside chats conducted by Pres. Franklin Roosevelt

1933–1944

In 1932, President Franklin D. Roosevelt was elected largely because he promised to help the country out of the Great Depression. To accomplish this he developed programs collectively called the New Deal.

But President Roosevelt needed to calm the fears and restore the confidence of Americans and to gain their support for the New Deal programs. To do this, he conducted a series of fireside chats: radio addresses to the American people about issues of concern. The informal chats made Americans feel as if President Roosevelt was talking directly to them. The fireside chats were the president’s unique way to harness the power of his bully pulpit.

The first fireside chat was on March 12, 1933. It addressed the banking crisis in which President Roosevelt tried to calm fears over bank closures and outline his plan to restore confidence in the banking system. The chats continued throughout his presidency, covering an array of topics.

Source: National Archives

Related Inquiry Packs:

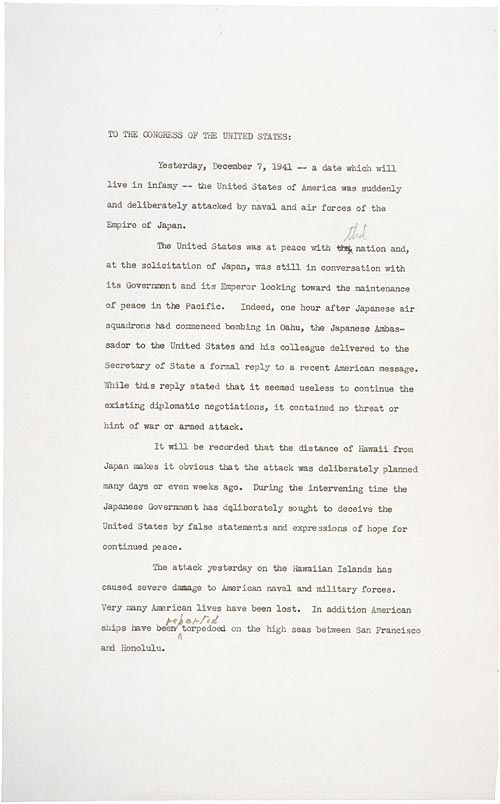

Declaration of war requested by Pres. Franklin Roosevelt

December 8, 1941

On December 7, 1941, the U.S. naval base in Hawaii was attacked by Japanese forces. More than 3,500 Americans were killed or wounded, and the Pacific fleet was almost completely destroyed.

At 12:30 p.m. on December 8th, President Franklin D. Roosevelt addressed a joint session of Congress and requested that Congress, which alone has the power to declare war, issue a formal declaration of war. His speech was also broadcast on the radio to a nationwide audience.

Congress passed the declaration of war with overwhelming support, and President Roosevelt signed it at 4 p.m. The United States officially entered World War II and joined the Allied Powers.

Source: National Archives

Related Inquiry Packs:

Executive Order 9066 ordered internment of Japanese Americans

February 19, 1942

On December 7, 1941, the Japanese military attacked the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, which was a U.S. territory. The next day, the United States formally declared war on Japan and entered World War II as part of the Allied Powers.

Two months after the attack on Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 in response to the fear that Japanese Americans were helping the Axis Powers by spying or sabotaging the U.S. war effort. Executive orders command a part of the executive branch, in this case the Department of War, to perform a task. They are not laws because they have not been passed in Congress, but they carry the same force as a law within the executive branch. The Supreme Court can use judicial review to strike down executive orders if they are found to violate the Constitution.

Executive Order 9066 was an area exclusion order that forced Japanese immigrants and Japanese Americans out of their communities on the West Coast and into internment camps. An internment camp imprisons large groups of people who have not been charged with or convicted of a crime.

Source: LandmarkCases.org

Related Inquiry Packs:

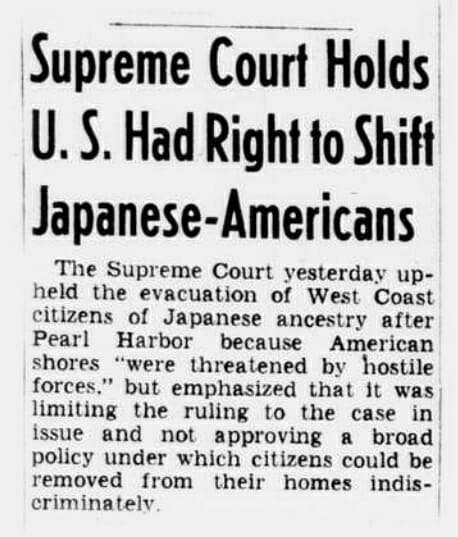

Korematsu v. U.S.: internment of people of Japanese descent found constitutional

December 18, 1944

After Pearl Harbor was bombed in December 1941, the military feared a Japanese attack on the U.S. mainland. The government worried that Americans of Japanese descent might aid the enemy. In 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order #9066 forcing people of Japanese descent living on the West Coast to leave their homes and businesses and relocate to internment camps to be imprisoned for the duration of the war.

Fred Korematsu, an American citizen of Japanese descent, was arrested and convicted of violating the executive order. Korematsu challenged his conviction in court arguing that the government did not have the power to force people to relocate to camps and that he was being discriminated against based on his race. The government argued that the evacuation was necessary to protect national security.

Korematsu’s case eventually made it to the Supreme Court. The Court agreed with the government and ruled that President Roosevelt’s executive order was constitutional. The Court found that the government’s war powers allowed it to force Japanese Americans and Japanese immigrants into internment camps. The Court stated that during wartime the government does not have the ability to determine if every single person is loyal to the United States or Japan. Therefore, it was appropriate to make a general decision regarding all people of Japanese descent because of the significant government interest in national security.

Many people considered this decision to be a stain on the Court’s legitimacy. Congress later passed a bill providing compensation for victims of this discrimination. While Korematsu v. United States has not technically been overturned, the Supreme Court has explicitly disapproved of it in Trump v. Hawaii (2018).

Source: LandmarkCases.org

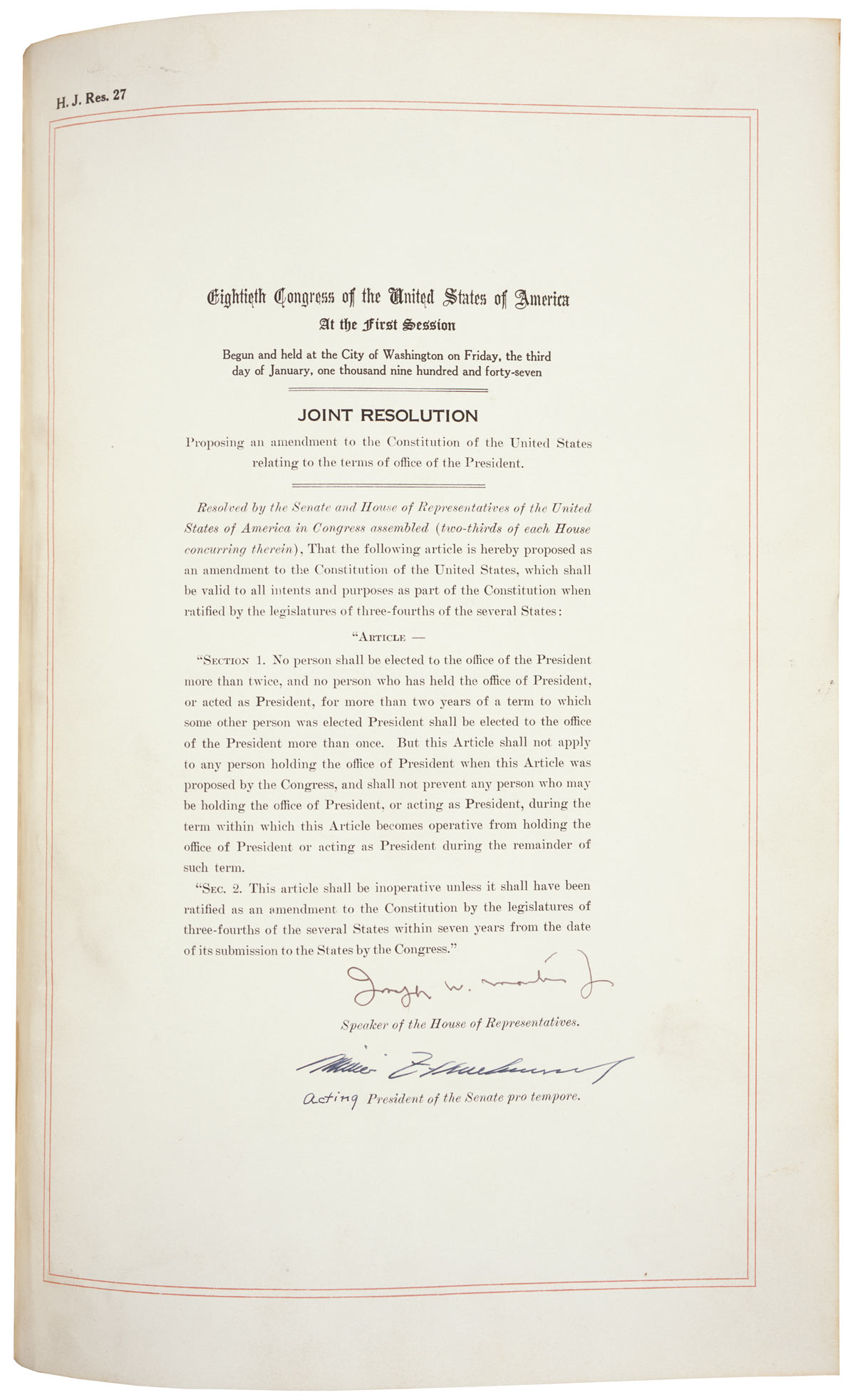

22nd Amendment ratified: presidency limited to two terms

February 27, 1951

The 22nd Amendment limits a president to being elected to a maximum of two terms. If a person becomes president due to succession and serves less than two years, they may be elected twice for a total of up to 10 years.

The 22nd Amendment made law President George Washington’s precedent of serving only two terms. President Washington’s precedent was broken only by President Franklin D. Roosevelt who was elected four times serving as president from 1933 to 1945.

Source: Congress.gov

Executive Order 10340: government took control of steel mills during Korean War

April 8, 1952

In 1950, the United States became involved in the Korean War, although no declaration of war was ever signed. Fighting this war required a large amount of steel to produce weapons, planes, ships, and other materials.

In 1951, a dispute arose between many of the largest steel mills and the steelworkers. The workers’ unions called for a strike if their demands were not met quickly. President Harry Truman met with Congress to explain his view that a strike would endanger national defense because steel was needed for the production of war materials. Congress did not take action or provide a solution that would keep the steel mills running during a strike.

The day before the strike was to begin, President Truman issued Executive Order 10340 directing his Secretary of Commerce to take control of the privately owned steel mills where the workers were threatening to strike so that they could continue producing steel. President Truman claimed that his power to take over the steel mills was constitutional because as commander-in-chief of the armed forces, he had the right to take any actions necessary to keep the armed forces operating.

Source: The American Presidency Project (UC Santa Barbara)

Related Inquiry Packs:

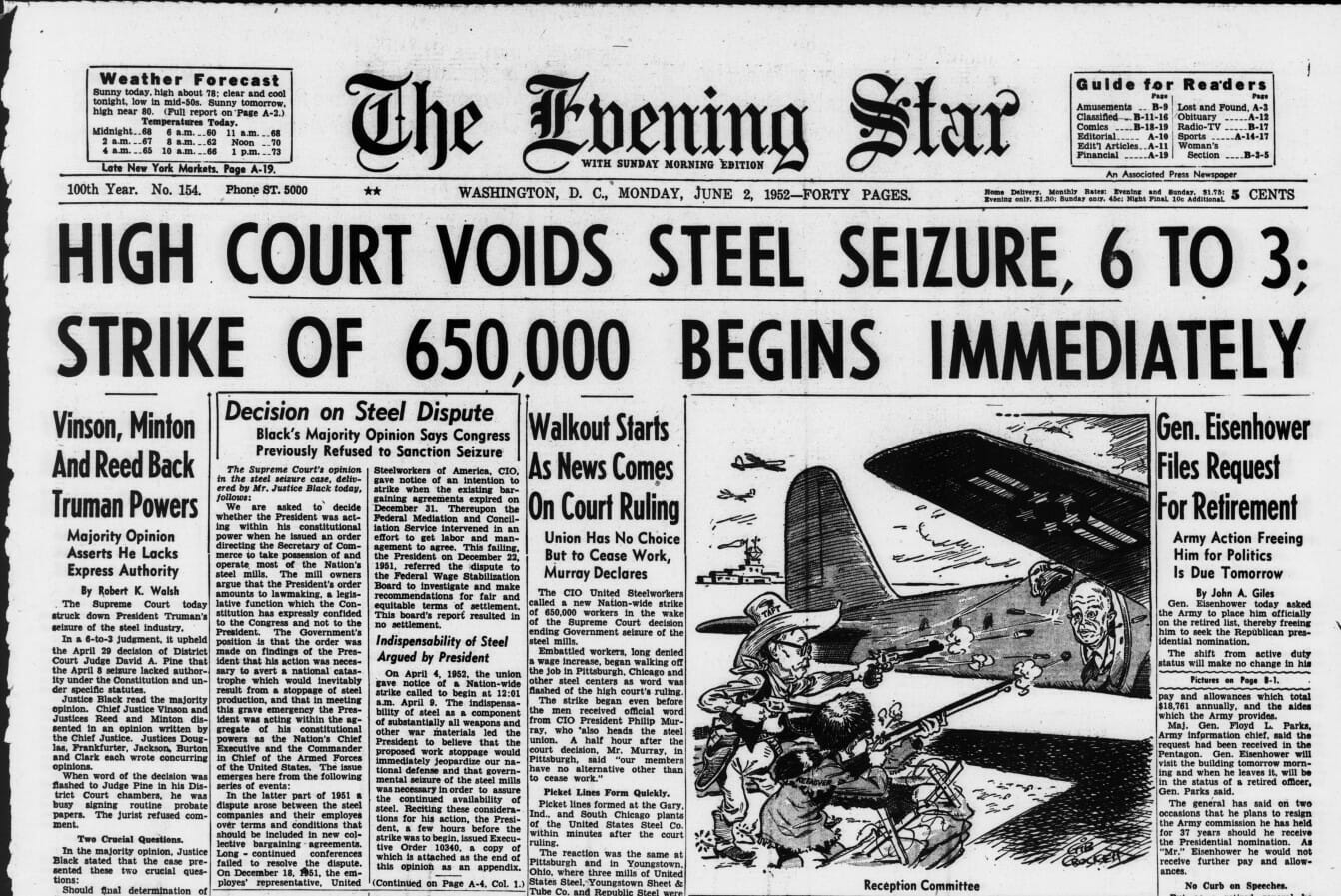

Youngstown Sheet & Tube Company v. Sawyer: Executive Order 10340 found unconstitutional

June 2, 1952

To ensure uninterrupted steel production during the Korean War, President Harry Truman issued Executive Order 10340: Directing the Secretary of Commerce to Take Possession of and Operate the Plants and Facilities of Certain Steel Companies. The steel mills sued and questioned the constitutionality of President Truman’s executive order.

The case went to the U.S. Supreme Court asking: Did the president have the constitutional authority to seize and operate the steel mills?

President Truman asserted that his commander-in-chief power authorized the government seizure and operation of the privately owned steel mills in order to prevent a strike during wartime.

Youngstown Sheet & Tube argued that Congress had not declared war against Korea, so President Truman could not take over privately owned steel plants based on the fact the United States was at war. The president had no authority to take private property unless Congress passed a law authorizing such an action.

The Supreme Court ruled that the president did not have the authority to issue the executive order and that Congress did not authorize President Truman to take possession of private property. The Court also ruled that the president’s power as commander-in-chief did not extend to labor disputes and strikes.

Source: Oyez

Related Inquiry Packs:

"60 Years Ago: Pres. Eisenhower on Little Rock School Integration 9-24-1957," C-SPAN, September 21, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZzT5v_ICU6I

Executive Order 10730: Pres. Eisenhower used federal troops to enforce Brown decisions

September 23, 1957

In 1954 in Brown v. Board of Education, the Supreme Court found unanimously that segregated public schools violated the Equal Protection Clause. As a result of this decision, all public schools had to desegregate. However, in a show of resistance, several states did not immediately desegregate their public schools. In 1955, a second case, Brown v. Board of Education II, directed schools and states to desegregate public schools “with all deliberate speed.”

Many states in the South participated in “massive resistance,” refusing to comply with the Brown decisions. In response, President Dwight D. Eisenhower issued Executive Order 10730, deploying the National Guard (federal troops) to Little Rock, Arkansas, to enforce the Brown rulings by escorting Black students into Central High School.

Source: National Archives

Related Inquiry Packs:

“Presidents v. Press: How the Pentagon Papers Leak Set Up First Amendment Showdowns | Retro Report,” Retro Report, February 2, 2022, https://www.retroreport.org/education/video/presidents-v.-press-how-the-pentagon-papers-leak-set-up-first-amendment-showdowns/.

New York Times v. U.S.: Pres. Nixon’s administration cannot use prior restraint

June 30, 1971

In 1971, a former government employee leaked a secret report outlining the history of U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War to the New York Times. This report, later known as the Pentagon Papers, contained many secret government documents.

The New York Times began to publish parts of the report to show that government officials had lied about the war in Vietnam. President Nixon’s attorney general obtained a temporary court order to stop publication of the papers, arguing that national security was at risk and the documents had been stolen.

The newspaper challenged the censorship and asked the U.S. Supreme Court to hear the case. Because the Nixon administration failed to prove a real threat to national security, the Supreme Court rejected the government’s claims that prior restraint was reasonable. The Court also ruled that the publication of the papers was protected by the First Amendment’s freedom of the press.

As a result of the decision in New York Times v. U.S., the government must show a clear national security threat to use prior restraint. It cannot censor the press simply because the information would reflect poorly on the government or nation.

Source: United States Government: Our Democracy (McGraw Hill Education)

"What Was the War Powers Resolution of 1973?," History, February 2, 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=barQHoh3krc

War Powers Resolution

November 7, 1973

The war in Vietnam was never formally declared a war by Congress; however, in every other sense of the word it was a war. Many Americans lost their lives fighting in Vietnam, and many believed the president should not have sent so many American soldiers to Vietnam without a formal declaration of war. Congress wanted to prevent this from happening again, so it passed the War Powers Resolution of 1973 (also known as the War Powers Act).

The War Powers Resolution sets several deadlines for the president to notify Congress and get congressional approval for sending troops to fight abroad. Since the Constitution gives war-making powers to both the president and Congress, the resolution remains controversial and many question its constitutionality. However, because the War Powers Resolution has never been invoked to force the president to withdraw troops, it has not yet been challenged in court.

Source: United States Government: Our Democracy (McGraw Hill Education)

Related Inquiry Packs:

U.S. v. Nixon: executive privilege not limitless

July 24, 1974

A congressional hearing about President Richard Nixon’s Watergate break-in scandal revealed that he had installed a tape-recording device in the Oval Office. The special prosecutor in charge of the case wanted access to these taped discussions to help prove that President Nixon and his aides had abused their power and broken the law. President Nixon claimed executive privilege and refused to hand over the tapes. President Nixon’s incomplete compliance with the special prosecutor’s demands was challenged and eventually taken to the U.S. Supreme Court. The Court decided that executive privilege is not limitless, and the tapes were released.

Source: LandmarkCases.org

Related Inquiry Packs:

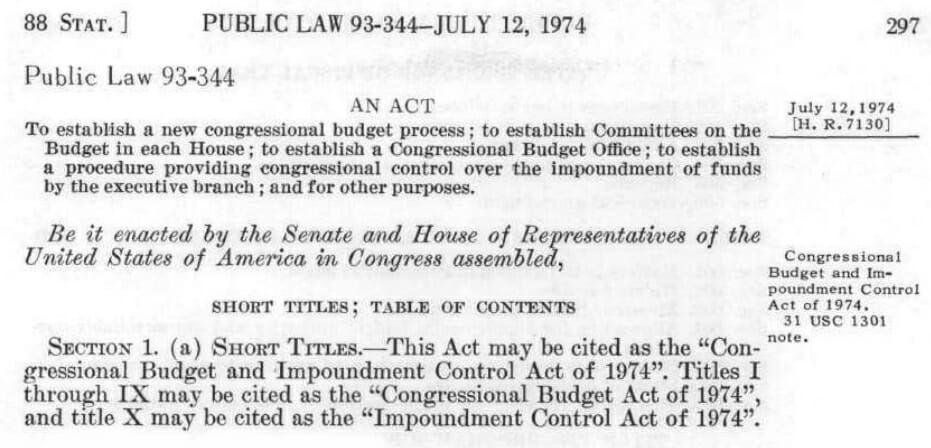

Budget and Impoundment Act of 1974

July 24, 1974

More often than earlier presidents, President Richard Nixon ordered executive agencies not to spend funds that Congress had appropriated for their use—a process called impoundment.

Congress, frustrated with President Nixon’s impoundment of congressionally appropriated funds, passed the Budget and Impoundment Act of 1974. This act changed the federal government's fiscal (financial) year from July 1 to October 1—a shift that allowed Congress a longer period of time to respond to the president's proposed budget.

The act also created the Congressional Budget Office that advises Congress on budget decisions, and it established budget committees in the House of Representatives and the Senate.

Source: History, Art, and Archives of the U.S. House of Representatives

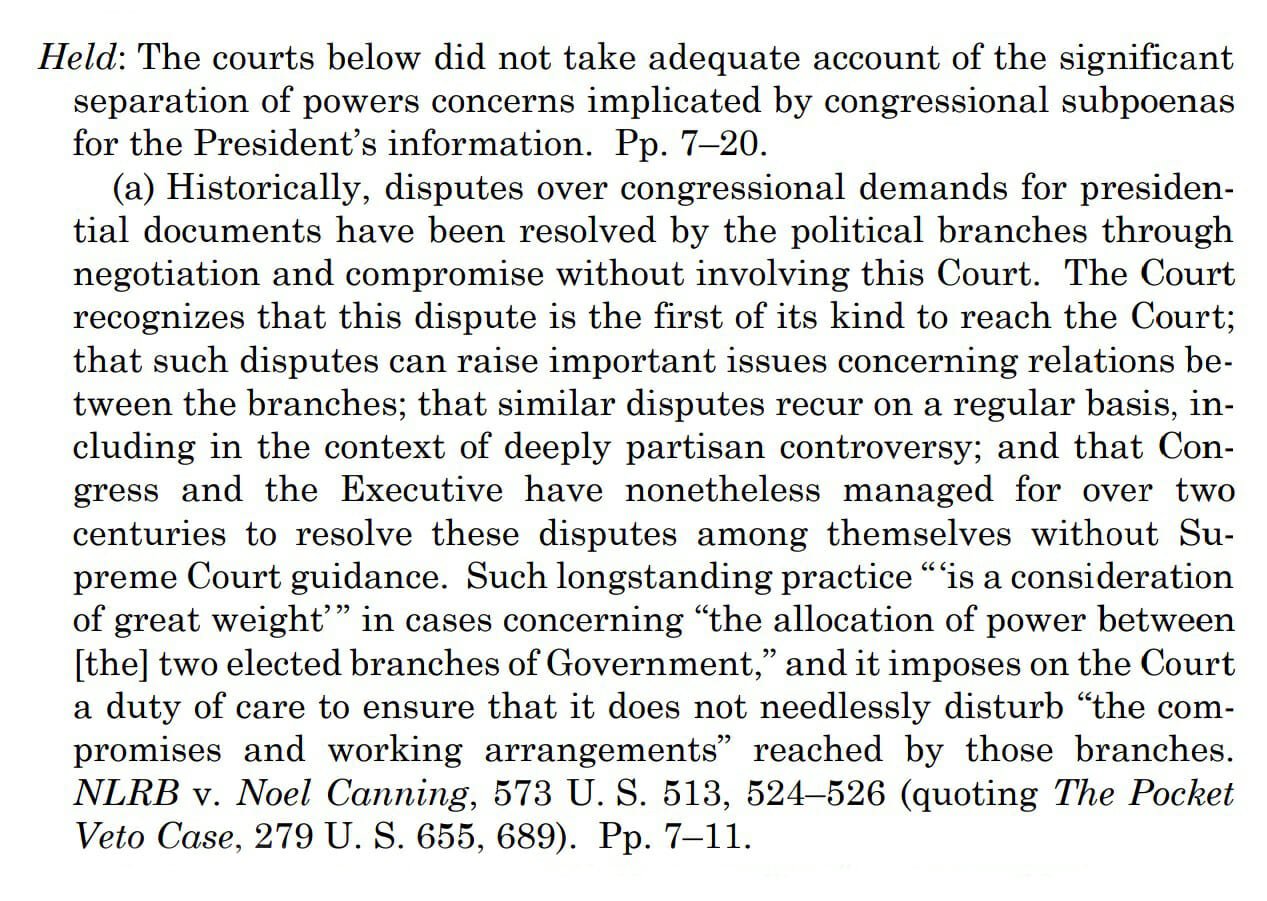

![08448v.jpg Thomas O’Halloran, “[President Gerald Ford appearing at the House Judiciary Subcommittee hearing on pardoning former President Richard Nixon, Washington, D.C.],” Photograph, October 17, 1974. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, https://www.loc.gov/item/2005678584/.](https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/pnp/ppmsca/08400/08448v.jpg)

Pres. Ford pardoned former Pres. Nixon

September 8, 1974

Gerald Ford was a member of Congress who replaced Vice President Spiro Agnew upon his resignation in October 1973. On August 9, 1974, President Richard Nixon became the first president to resign from office. Vice President Ford was sworn in as his replacement. President Ford became the first person to become president without being elected to the executive branch.

Although President Nixon had yet to be charged with a specific crime, on September 8, 1974, President Ford announced his decision to “grant a full, free, and absolute pardon unto Richard Nixon for all offenses against the United States which he, Richard Nixon, has committed or may have committed.” The pardon was met with mixed reactions, some supportive and some outraged because they believed the pardon was a secret deal between Presidents Ford and Nixon.

To answer questions about the pardon, President Ford gave testimony before the House Judiciary Committee’s Subcommittee on Criminal Justice. This made him the first president to give sworn congressional testimony.

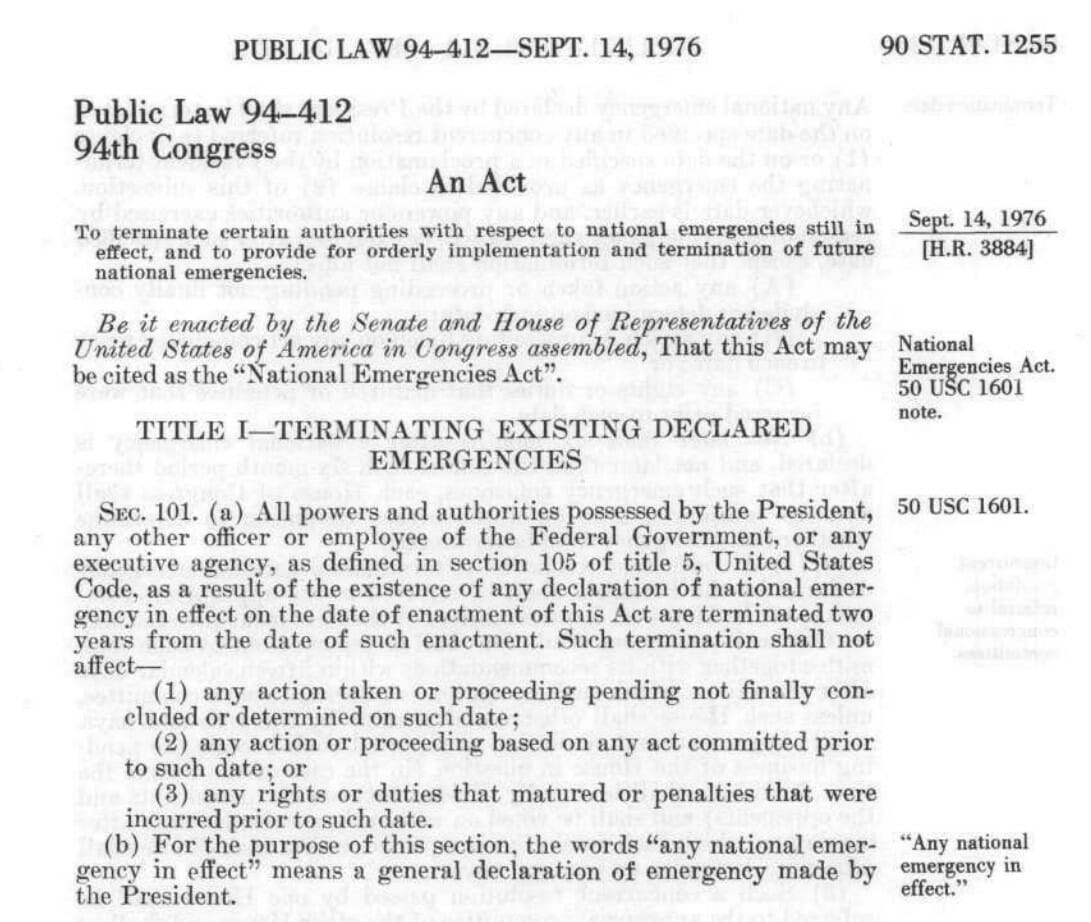

National Emergencies Act

September 14, 1976

In 1974, as a reaction to the expansion of the war in Vietnam, Congress created the Special Committee on National Emergencies and Delegated Emergency Powers. The committee studied the powers that had been delegated to presidents in national emergencies. The committee found 470 powers Congress had granted to presidents in times of emergencies such as economic depression and war.

The committee found that in a few instances the U.S. Supreme Court had limited presidents’ emergency powers such as Youngstown Sheet & Tube Company v. Sawyer, but Congress had rarely done so.

As a result of the research, Congress passed the National Emergencies Act ending four existing states of emergency and adding accountability and reporting requirements for presidents in future emergencies.

Source: United States Senate

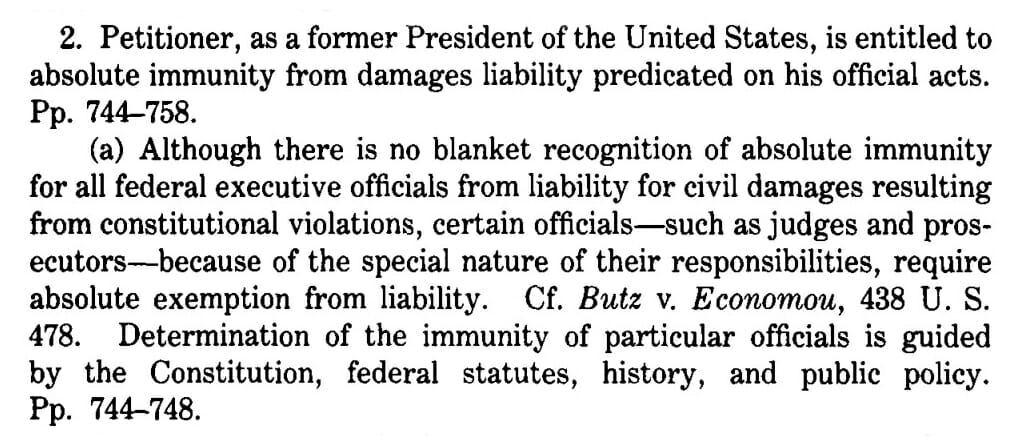

Nixon v. Fitzgerald: presidents found immune from liability for damages resulting from official acts

June 26, 1982

In 1968, a civilian analyst named A. Ernest Fitzgerald testified before a congressional committee about inefficiencies and cost overruns within the U.S. Air Force. He was later fired, and President Richard Nixon took responsibility for his dismissal. Fitzgerald sued President Nixon for damages after a commission concluded that his firing was unjust.

The U.S. Supreme Court was asked to decide: Was the president immune from prosecution in a civil suit?

The Court ruled that a president has absolute immunity from liability for damages resulting from official acts. The Court reasoned that immunity was part of separation of powers between the branches of government.

Source: Oyez

Line Item Veto Act signed into law by Pres. Bill Clinton

April 9, 1996

A line-item veto provides a president or governor with the power to reject specific provisions in a bill. Many state constitutions grant the governor the power to use the line-item veto on state budgets. The U.S. Constitution does not explicitly grant the president that power.

In 1996, the Republican Congress passed, and Democratic President Bill Clinton signed into law, the Line Item Veto Act. The Act allowed the president to cancel certain types of revenue (spending or tax benefits) provisions in the bill within five days after signing a bill. The president was then required to send a message to Congress regarding the cancellation. Congress could “override” the line-item veto by enacting a disapproval bill.

Many immediately questioned the constitutionality of the Line Item Veto Act because the Presentment Clause in Article 1 of the U.S. Constitution only provides for the president to sign a bill into law, veto it, or ignore it (becoming law without the president’s signature if Congress remains in session or becoming a pocket veto if Congress adjourns within 10 days). The act was later struck down in Clinton v. City of New York (1998).

Source: United States Senate

Clinton v. Jones: president’s immunity from civil suits found to not extend to unofficial acts

May 27, 1997

Paula Jones sued President Bill Clinton. Jones alleged that, while he was governor of Arkansas and she was an employee of the state, President Clinton harassed her with unwanted sexual advances. Jones claimed that her rejection of his advances resulted in punishment from her state employers.

By the time of the lawsuit, Clinton was elected president. President Clinton sought to invoke presidential immunity to completely dismiss the lawsuit against him. Until his request to have the suit dismissed could be settled, he requested that the suit be suspended until after his presidency. The suspension was granted, and Jones appealed.

The case ultimately went before the U.S. Supreme Court asking: Is a serving president, for separation of powers reasons, entitled to absolute immunity from civil suits arising out of events that took place prior to his taking office?

The Court ruled that the president’s immunity from civil suits did not extend to cases involving unofficial acts. This case allowed the Paula Jones sexual harassment case against Bill Clinton to proceed.

Source: Oyez

Related Inquiry Packs:

Clinton v. City of New York: Line Item Veto Act found unconstitutional

June 25, 1998

After the passage of the Line Item Veto Act, President Bill Clinton, used the veto to cancel provisions of the Balanced Budget Act of 1997 and the Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997. Groups affected by the provisions challenged the constitutionality of the Line Item Veto Act arguing that the Presentment Clause in Article 1 of the U.S. Constitution only provides for the president to sign a bill into law, veto it, or ignore it—not to amend it by striking items.

The case ultimately went before the U.S. Supreme Court asking: Did the president’s ability to selectively cancel individual portions of bills under the Line Item Veto Act violate the Presentment Clause of Article 1?

The Court declared the Line Item Veto Act, and therefore the president’s short-lived line-item veto power, unconstitutional as a violation of the Presentment Clause. It explained that by giving presidents the power to use the line-item veto, the act in effect gave them the power to amend the laws, which violated the legislative process set out in Article 1.

Source: Oyez

Clinton v. City of New York: Line Item Veto Act found unconstitutional

June 25, 1998

After the passage of the Line Item Veto Act, President Bill Clinton, used the veto to cancel provisions of the Balanced Budget Act of 1997 and the Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997. Groups affected by the provisions challenged the constitutionality of the Line Item Veto Act arguing that the Presentment Clause in Article 1 of the U.S. Constitution only provides for the president to sign a bill into law, veto it, or ignore it—not to amend it by striking items.

The case ultimately went before the U.S. Supreme Court asking: Did the president’s ability to selectively cancel individual portions of bills under the Line Item Veto Act violate the Presentment Clause of Article 1?

The Court declared the Line Item Veto Act, and therefore the president’s short-lived line-item veto power, unconstitutional as a violation of the Presentment Clause. It explained that by giving presidents the power to use the line-item veto, the act in effect gave them the power to amend the laws, which violated the legislative process set out in Article 1.

Source: Oyez

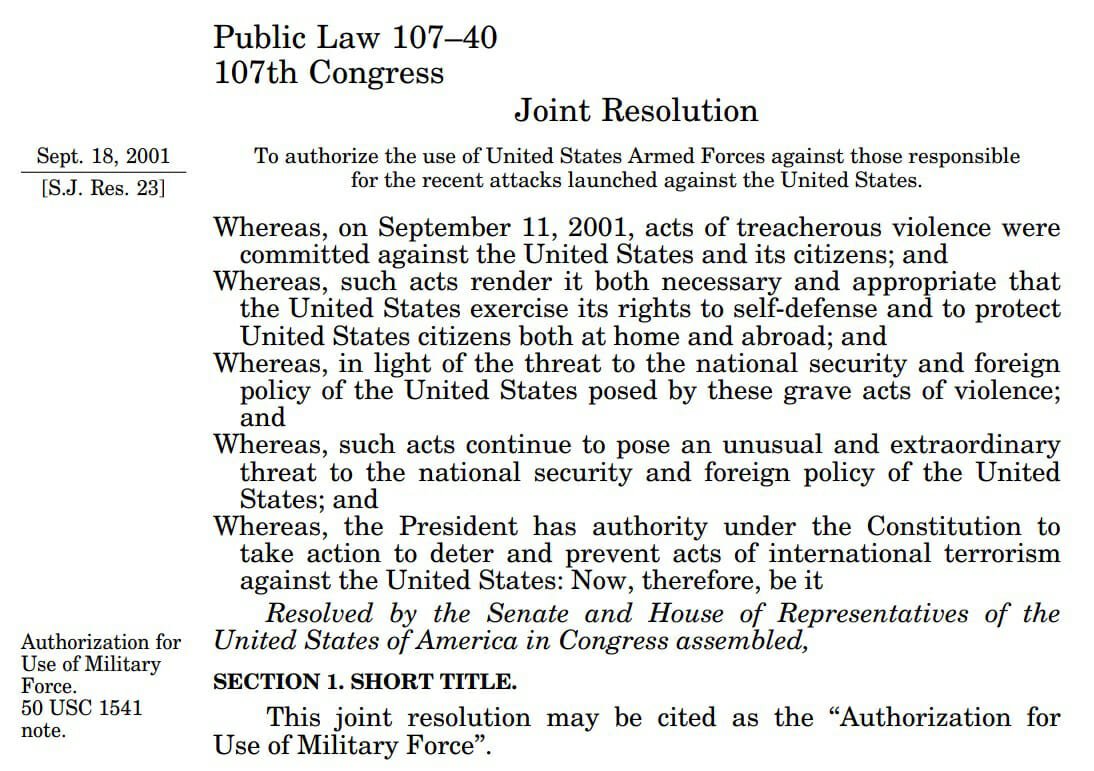

Authorization for Use of Military Force passed by Congress

September 18, 2001

On September 11, 2001, terrorists flew planes into the Twin Towers in New York City and the Pentagon just outside of Washington, DC. Another plane hijacked by terrorists crashed into a field in Pennsylvania after passengers on board heroically stopped them from reaching their intended destination, likely the U.S. Capitol building.

In the days immediately after the September 11th attacks, a joint resolution of Congress was passed authorizing President George W. Bush to take military steps to deal with the parties responsible for the attacks on the United States. President Bush signed the measure into law on September 18, 2001.

The Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF) authorized the president to use all necessary and appropriate force against those nations, organizations, or persons he determined planned, authorized, committed, or aided the terrorist attacks, or harbored such organizations or persons, in order to prevent any future acts of terrorism.

Unlike all other major legislation, the AUMF authorized the president to use military force against not only nations but also organizations and individuals, which was unprecedented in American history.

Source: EveryCRSReport.com

Related Inquiry Packs:

DACA established by Pres. Obama

June 15, 2012

President Barack Obama encouraged Congress to pass the Dream (Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors) Act but was unsuccessful. In 2012, the Obama administration issued an executive branch memorandum creating the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) policy. DACA allowed youth living in the country illegally who fulfilled certain requirements to be protected from deportation, receive a work permit, and qualify for a driver’s license.

This policy was controversial for many reasons including whether the administration had the authority to bypass Congress to implement this policy with the use of an executive branch memorandum. It was challenged in court during the Obama administration, but the challenges were never fully resolved.

Sources: Library of Congress and The Obama Whitehouse

Related Inquiry Packs:

Proclamation No. 9645 signed by Pres. Trump; travel into U.S. restricted

September 24, 2017

Proclamation No. 9645 was an executive order by President Donald Trump that restricted travel into the United States from eight countries: Chad, Iran, Libya, North Korea, Somalia, Syria, Venezuela, and Yemen. In the proclamation, President Trump stated that, “As President, I must act to protect the security and interests of the United States and its people.”

This proclamation was issued after earlier travel bans were struck down as unconstitutional in part based on First Amendment religious freedom rights.

Source: Immigration Policy Tracking Project

Related Inquiry Packs:

Trump v. Hawaii: Pres. Trump’s travel restrictions found constitutional

June 26, 2018

In Trump v. Hawaii, Proclamation No. 9645 was challenged at the U.S. Supreme Court. Hawaii argued that President Donald Trump was attempting to exercise power that neither Congress nor the Constitution gave to the presidency.

Among other questions, this case asked the Court: Does the president have the authority under the Immigration and Nationality Act to issue the Proclamation?

The Court ruled that the Immigration and Nationality Act gave the president “broad discretion” to suspend the entry of non-citizens into the United States. Therefore, the Proclamation did not exceed the power of the president and the travel restrictions were permitted to stand.

Source: Oyez

Related Inquiry Packs:

DHS v. Regents of the Univ. of CA: Trump administration did not properly phase out DACA

June 18, 2020

In 2012, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) under President Barack Obama adopted a policy known as the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), which postponed the deportation of immigrants who had been brought to the United States as children without proper documentation.

In 2017, the Trump administration replaced the Obama administration and began to phase out DACA. The Trump administration stated that the Obama administration had created DACA “without proper statutory authority and with no established end-date” making it an “unconstitutional exercise of authority by the Executive Branch.”

The University of California challenged the Trump administration policy, alleging that the phasing out of DACA did not follow procedures set out for the executive branch in the Administrative Procedures Act (APA) including one requiring “reasoned analysis” for such changes.

The case ultimately came before the U.S. Supreme Court asking: Is DHS’s decision to wind down the DACA policy lawful?

The Court found that the Trump administration’s attempt to phase out DACA violated the APA because they did not supply reasoned analysis for doing so. However, the Court did not decide whether DACA was within the scope of the president’s constitutional powers.

Source: Oyez

Trump v. Mazars USA: Congress can subpoena president’s private financial records

July 9, 2020

A committee in the U.S. House of Representatives issued a subpoena to President Donald Trump’s accounting firm. The subpoena ordered the firm to hand over private financial records belonging to President Trump and involving some of his businesses.

The committee stated it needed the records as part of its investigation into whether Congress should amend its ethics laws. President Trump argued that the information would serve no legitimate purpose and that except for impeachments, Congress does not have the authority to investigate a sitting president’s possible conflicts of interest and violations of law. He sued to prevent the accounting firm from turning over the documents.

The case came before the U.S. Supreme Court asking: Does the Constitution prohibit subpoenas issued to Donald Trump’s accounting firm requiring it to provide financial records?

The Court ruled that courts should consider the separation of powers between the president and Congress and assess four factors when deciding whether a subpoena can be issued on a sitting president:

- whether the information is available elsewhere

- whether the subpoena is no broader than reasonably necessary

- whether Congress has offered evidence to “establish that a subpoena advances a valid legislative purpose”

- what burdens a subpoena imposes on the president

The Supreme Court sent the case back to the lower court to consider these factors and the separation of powers between the president and Congress. The case was not resolved before the 2020 election so became moot.

Sources: Just Security and Oyez

Related Inquiry Packs: